the working man's friend and the royal peculiar

by Tim Walker

I completed my PhD in Earth Sciences at UC Santa Barbara in 1984, when OPEC was falling apart and oil prices were in free fall. Laid-off oil company geologists packed the academic job fairs where I sought future employment, and in the end I fell back on a computer programming job in Fullerton, California. My wife Pat and I, when we realized we had little choice but to move to Orange County, were heartbroken and wept in each other’s arms.

Two years later, I was laid off from the programming job and took a tech-support job in Santa Barbara. By this time, I was keeping my advanced degree a secret from potential employers. Even the joy of moving back to our true home, where we had met and married and lived our best life, was not enough to save me from depression as I took another step down the career ladder.

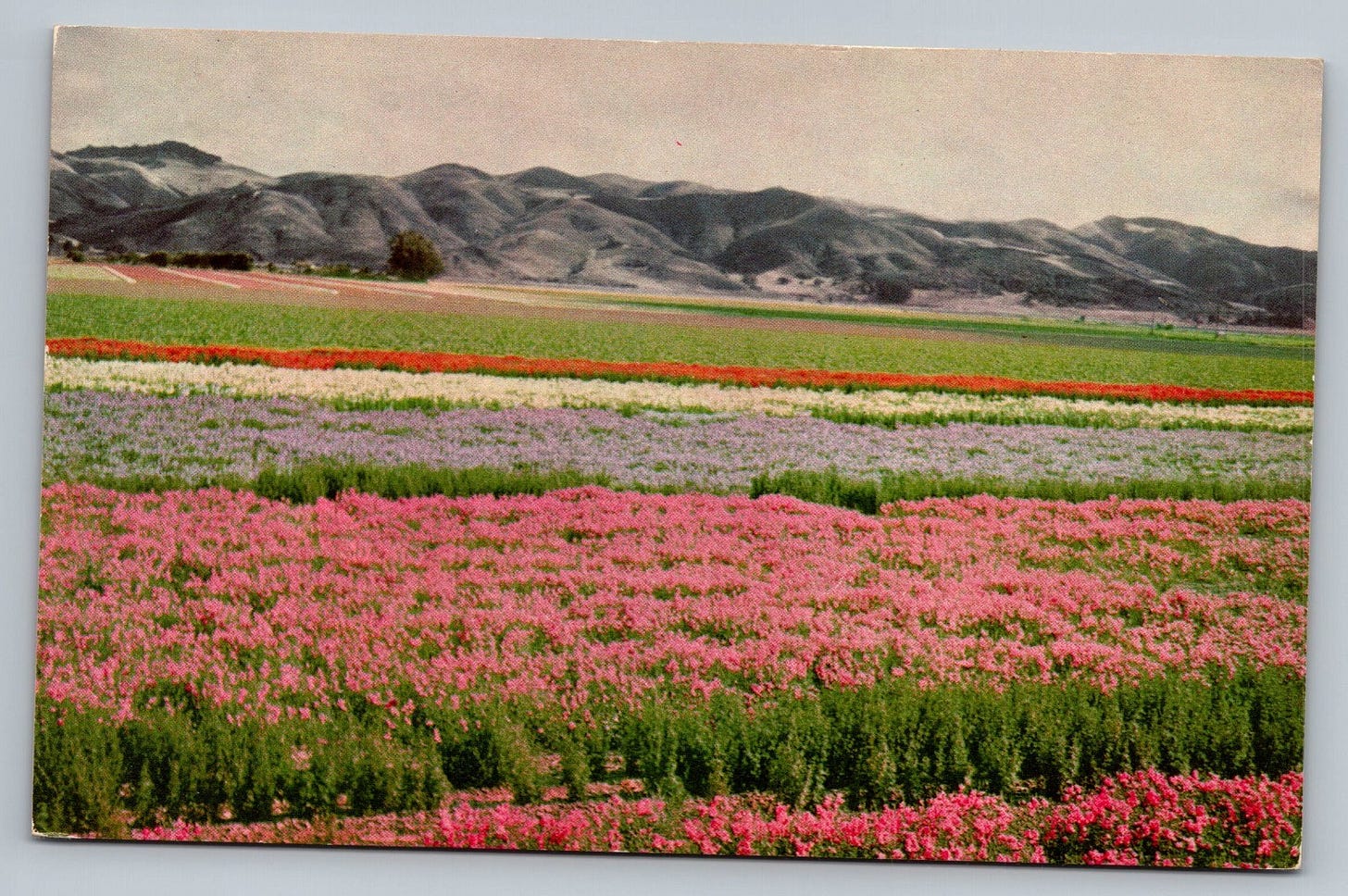

But the possibility of owning our own home distracted me from career angst. We couldn’t touch the pricey coastal real estate in Santa Barbara, but we could afford a house in Lompoc, an inland town in a valley framed by hills cloaked in chapparal and filled with orchards and flower fields, where delphiniums, stock, and sweet peas were grown for seed. It had a nice small-town feel, but the move came with a new drawback: a daily commute of an hour each way to our jobs in Santa Barbara. I had chronic back pain at the time, too, and was in the habit of taking a hot bath in the morning and doing stretches after I cooled down, adding about an hour to my morning ritual. To make matters infinitely worse, I was put on the early shift, to answer support calls from Europe, and had to be in the office at 6:00 a.m. This meant that, in order to get a decent night’s sleep, we had to go to bed when most people’s day is starting to get interesting. I wasn’t often able to do this.

A few years later, I landed a good programming job in Santa Barbara. So, no more super-early hours—but by that time our newborn son was on a rapid cycle of naps, feedings, and eliminations around the clock, not to mention his persistently stupendous colic, which featured motiveless inconsolable crying, especially late in the day, while we were at our wits’ end trying to find the magic combination of cuddling, rhythmic motion, verbal reassurances, and background noise (running the dishwasher sometimes seemed effective) that would calm him. When he outgrew some of these infant tribulations and took more of an interest in the world around him, he hated to fall asleep, and it took endless coaxing, walks around the block in the stroller, rides in the car seat, or just hovering wearily over him in his crib reading bed-time stories, to lull him to sleep.

Pat and I were becoming intimate with “local sleep,” a state of consciousness in which limited parts of the overburdened brain fall into a sleep-like state. I would be awake enough to sit in the office and construct computer logic, methodically nesting if/then statements ten deep, and the next moment have a conversation like this at the water cooler:

Me: “Let me borrow your newspaper during lunch? I won’t do the crossword puzzle—not in ink, anyway.”

Colleague: “You’d do my crossword puzzle in ink?”

And I wouldn’t bother to correct her, because in dream logic a negation, by the very act of raising or dwelling on the subject, is also an affirmation.

Another convention of dream logic is the blurring of boundaries between the self and other. The first rule of dream interpretation is to find something of yourself in everything you dream about, to realize that every person and presence in your dream is a part or aspect of yourself. This blurring of boundaries led me to have detailed waking fantasies about what it would be like to live the life of someone else: a man I didn’t know—and didn’t want to know. I could only see the superficial facts of his life as he went about his business in the neighborhood where we lived.

His business was the salvage, sale, and installation of used tires. He styled himself “The Working Man’s Friend,” as it said on his truck, a small flat-bed with sides made from salvaged lumber. I guess he had a place of business, perhaps at his home, where he stored and mounted tires, repaired flats, and so on, but I never knew it. I’d see him with his truck, which he usually parked at a strip mall near our house to advertise his business.

There was, between The Working Man’s Friend and me, a symmetry of difference. Physically, he was slender and wiry, while I was podgy and soft. I had no vices, except drinking coffee and buying books, and he literally wore his vices on his sleeve, in the form of a pack of cigarettes rolled in the sleeve of his T-shirt, along with a general air of dissolution. He had probably never been good in school, while I had my PhD. I was a “knowledge worker,” and he had a semi-skilled trade. He was an entrepreneur, and I was a cog in a corporate machine. I was resignedly underemployed, while he appeared to relish the role in society conferred by his business. Perhaps all these differences could explain my obsession, which was almost a non-erotic crush. By becoming The Working Man’s Friend, I could transcend all the things about my existence I found limiting, unrewarding, and exhausting.

Or maybe it was just a trick of word association by which I, the worn-out, tired guy, was inspired to become the worn-but-still-has-some-tread-on-it tire guy.

Ideally, to become The Working Man’s Friend, I would magically inhabit his body, like a malign spirit in possession of some poor sap, and do my best to carry on as he was accustomed. This was satisfying, but at times I also considered how I might manage the thing as an alternative future of my own life. I had to wonder if it was remotely possible for me to rise to the physical demands of his job. And what would I have to do to get that lean and ravaged look? If changing your body type was easy, everyone would do it; besides, superhuman self-restraint didn’t seem like a part of The Working Man’s Friend’s persona. The best I could hope for was some degree of the ravaged look, which should follow from the cultivation of his smoking and presumed drinking habits. First, a major adjustment of attitude was called for, because like most ex-smokers I was disgusted by the sight of someone smoking and intolerant of the merest whiff of their smoke. I can tell if someone is smoking in the car ahead of me on the highway and will change lanes to get away from their slipstream of noxiousness. This aversion is very much in favor of my experiment, because by the time I’ve taught myself to enjoy smoking again, and to rationalize the pariah status that comes with it, I’ll be well on my way to channeling the spirit of The Working Man’s Friend.

Other forms of discipline in aid of the transition would be to take an interest in sports, to watch a lot of television, and presumably to hang out in dive bars. Ever since my first wife cleared off and took the TV with her (it was a gift from her parents), I had not owned or wanted one. Suffice it to say that thus far in life I had not indulged any of these three habits to the slightest degree. The sports and TV would give me a common language to speak with the cronies appropriate to The Working Man’s Friend’s station in life, who I’d meet in the dive bars, and perhaps help to dull my prickly intellect down to a point where I could tolerate the company of other barflies. (Or, to put it another way, these steps might succeed in making me normal enough to enjoy the sociability of a neighborhood bar.)

My wife and child didn’t appear in these fantasies, but in retrospect it would have been consistent with The Working Man’s Friend persona to simply refuse to do the “women’s work” of childcare, housework, and general reliability, and insist on the working man’s prerogative of boozing it up with some chums after a hard day’s work. Then Pat could either channel my working-class counterpart and suck it up, or—more likely—she would divorce me. Either way, I’d be free of much of the drudgery of family life.

The transgressive nature of these fantasies was never lost on me. If I made assumptions about The Working Man’s Friend’s disadvantages, his resentments and discontents, then I risked doing him an injustice. But absent his lifetime of experiences and hard lessons, the adoption of his persona would be superficial. Even so, he didn’t deserve my condescension, my stereotyping. My project reeked of the recently-articulated sin of cultural appropriation. Blaming sleep deprivation allows me to live with this.

My mother was born in Canada and had dual citizenship, which technically makes me a Canadian citizen. With the rise of Trumpism, I’ve been thinking about asserting my Canadian citizenship. Not that I want to move to Canada—but one of the perks of citizenship would be to enjoy a certain psychic distance from the disorderly political life of my native country. This urge somehow translated itself into a fixation on the Dean of Westminster, after I read about him in a magazine article. It struck me that he must live in an atmosphere of luxury and great personal power, kind of like Don Corleone in the opening sequence of The Godfather, but without the element of criminal conspiracy, and that this would be a very pleasant existence. Filling the Dean’s shoes is an aspiration rather than, as in the case of Working Man’s Friend, a case of slumming, so it seems much less offensive.

The first, but not the most difficult, barrier to my transformation into the Dean of Westminster, is that I’m not a British subject. Actually, I can’t even imagine what it means to a subject of the sovereign, as opposed to the citizen of a democracy. The practical differences seem to be few, but there are lots of quaint throwbacks in the names of things, like receiving your parcels and letters through the Royal Mail. Westminster Abbey is a “Royal Peculiar,” not subject to the normal hierarchy of the Anglican Church, but answerable directly to the monarch as the titular head of the Church of England, so I suppose some feeling of feudal allegiance to the royal family would be an important qualification for the position of Dean of Westminster. But all this must be covered in the naturalization process, so there’s no need to brush up on it in advance.

It would seem a point against me that I have no use for religion and no history of churchgoing; but I only lack a sincere conversion to become a member of the Church of England in good standing.

The strongest barrier is going to be the educational requirements. I have never been much good at languages, and I think the Dean of Westminster is expected to be a Latin scholar and be able to read scripture in Hebrew and Greek, maybe even Aramaic. But I tell myself, it’s all a matter of motivation. I would shine at ancient languages if it were important to me. Attendance at an elite British university, and the study of theology, would also be expected. It’s questionable whether, at my age (77 this year), I could accomplish all this in the time remaining to me.

I take heart from the experience of the self-titled Baron Corvo, born Frederick William Rolfe, the English eccentric and writer. His novel Hadrian the Seventh (1904) recounts his elevation, despite not being a priest or even raised a Catholic, to the position of Pope of the Catholic Church, and his subsequent complete vindication in his struggles against a lifetime of detractors and betrayers. Although this was pure fantasy, Baron Corvo was prescient in his supposition that the papacy would become open to candidates other than the Italians who monopolized it since 1523. John Paul II, formerly the Polish Cardinal Karol Józef Wojtyła, was elected Pope in 1978, and the current holder of the title, Pope Leo XIV, is the former Robert Francis Prevost, who was born in the United States.

It’s reasonable to assume that the Church of England too might want to expand its international appeal by recruiting and elevating clerics with less parochial origins and outlook than custom has hitherto required. Or maybe not—but that’s my story, and I’m sticking to it.

God save our gracious King, and bless his dear old heart!

About the author:

Tim Walker read, for pleasure, the complete novels of Charles Dickens while earning a BA in Environmental Studies, and the complete novels of Anthony Trollope while earning a PhD in Geological Sciences, and has worked as a computer programmer, healthcare data analyst, used book seller, and pet sitter. He lives largely in his own head, while he corporeally resides in Santa Barbara with his son Dana and their cat Cassiopeia. His essays and poems most recently appeared in Harpy Hybrid Review, 3:AM, Fatal Flaw, Rock Salt Journal, New Verse Newsletter, and TYPO: The International Journal of Prototypes.

This is a delight in the clothing of a historical reminder, several fantasies, and utter weirdness. Thanks for this.