jealous of my friend's dad's funeral

by Jennifer Phillips

LAST YEAR, after having just moved in with my boyfriend, I’m so jealous that I can’t sleep.

The sheets are crisp beneath me, and the humidifier puffs soft clouds into the dark room. My black cat is curled like a shadow at my feet while my partner snores lightly beside me. Despite the calm, I can’t settle. I twist and turn as jealousy smolders inside my gut, so hot I half expect the sheets to singe.

I think about a friend of mine whose father was diagnosed with cancer—one of the bad ones, the kind that gives you a countdown. My friend dropped everything and moved home. He and his dad had conversations that would have otherwise gone unsaid, and he held his dad’s hand as the chemo drained life from his body.

His father celebrated one final Christmas, put his affairs in order, even chose the meal for his wake—roast lamb and the coconut cake he’d requested every birthday. He passed away in his own bed, wrapped in the scent of home.

A week later, the pews overflowed. The line for calling hours curled around the stone building like a ribbon. “Gone too soon,” they all whispered. Gone too soon, sure, but gone exactly how many of us hope: A farewell cradled in love, orderly and complete.

This kind of death is tragic but tidy.

I roll over in my sheets, giving up on sleep.

It’s different when someone dies slowly.

My cat, annoyed by my restlessness, slips off the bed and past the moving boxes crammed with my notebooks and his engineering textbooks. She slinks out into the empty living room—we have yet to unpack—searching for quieter rest.

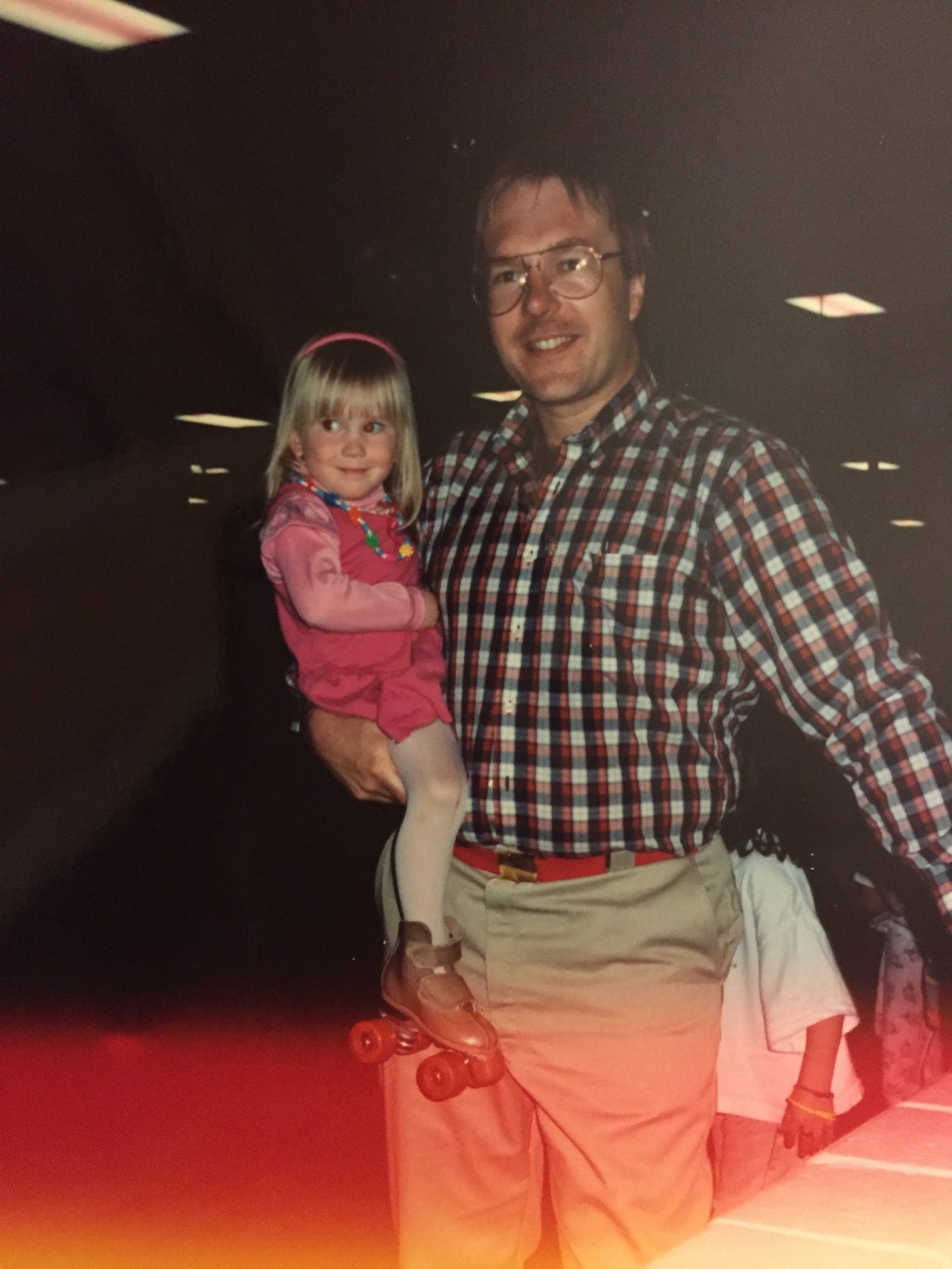

Before my dad was diagnosed thirteen years ago, Parkinson’s was just a vague idea to me—a slight tremor in the hands of the woman at church pouring coffee, Michael J. Fox smiling through interviews on late-night TV. I was twenty-four and had just embarked on an adventure teaching English halfway across the world in South Korea. I sat alone in my small apartment in Chuncheon, a city an hour north of Seoul, as my parents told me the news over a grainy Skype call. A sick parent was the last thing on my mind, and I didn’t know what to do with the information.

I didn’t know that over the following decade Parkinson’s would dismantle my dad piece by piece—stealing his balance, blurring his speech, clouding his mind, locking his muscles like a rusted hinge.

My family and I have become students of this slow erosion. We’ve memorized every brutal symptom. We’ve also come to know a quieter grief—the kind that slips in unnoticed, and then never leaves. There are shelves of books written about it. They call it the “long goodbye,” although I’ve always thought the name seems too gentle and sanitized for something so cruel.

Ambiguous grief doesn’t fit neatly on a Hallmark card. It’s messy and confusing and shapeless, stretching over years, blurring the lines between love and loss. How do you mourn someone who is still alive? When does it start and when does it end?

Did it begin the day he was diagnosed? Or when the doctor suggested he stop driving? Maybe the Christmas I came home to find they had installed the grab bars—on the shower wall, by the toilet, on his bed—so he could anchor himself, rocking his body just to move the way he once did.

The day the walker showed up. Then the wheelchair.

Perhaps it was the moment my mom told me he was locked out of his iPhone. I laughed, “You know he’s a Boomer—technology isn’t his thing,” until she softly reminded me his passcode was his own birthday.

Maybe it was the night my family finally uttered the word “dementia” aloud on the phone, although we had all silently carried it in our hearts for a year. Or maybe the next morning when I arrived at work to confused co-workers, eyes swollen, blood vessels burst across my orbital bone—a side effect of sobbing harder than I ever have.

Maybe it happened when his golf buddies stopped calling, when the dinner invites for my parents thinned out, then ceased altogether.

Or was it the day I opened my thirty-third birthday card and saw it signed only, “love, Mom.” For the first thirty-two years of my life, it was always signed “love, Mom and Dad.” But my dad wasn’t dead, he was still alive somewhere—but fading, a body without its map, a mind wandering too far to come back.

How do you make sense of the slow, relentless grief? You don’t. You keep living your life. You go on first dates, but dread the moment the conversation steers to your family and they ask, “so, are you close with your parents?”

You take a long sip of your martini, and simply say “yes, and you?” because talking about an ailing parent is far from cool or sexy and you don’t want to tell your date that your dad is dying alone in a nursing home, and your mom cries every day.

You try to stay healthy. You eat your greens, you take your vitamins. You sign up for a 5K you don’t care about. But still, you find yourself in the doctor’s office—six times in two months—convinced your body is betraying you. Ovarian cancer, MS, Leukemia. You’ve Googled them all. Because if it happened to him, why wouldn’t it happen to you?

After countless first dates and martinis and nights you crawl into bed feeling hollow, someone stays.

You laugh for hours on a sunny rooftop, sharing stories and a bottle of rosé. You learn he spends his Saturdays volunteering and he treated his parents to a trip to Turkey last summer. You look at his broad shoulders and wonder what it would be like to kiss him. "You’re funny," he texts later.

He cooks you carbonara and remembers you love tulips. He desperately tries to win over your cat. But he’s not just there charming your friends at dinner parties, he’s there when you crumble afterwards, and he walks you home to your apartment, holding you as you quietly weep into his chest. For the first time, you envision someone being the father to your future children that your dying father was to you.

You visit the nursing home when you can, a Tuesday in March. You’re in town for family, but if you’re being honest, you’ve been avoiding this part of the trip. “St. Ann’s is really nice, my grandma was there,” a friend offers. You want to scream Yes, your grandma. This is my dad, he’s not even seventy. Grandmas are supposed to be in St. Ann’s, but instead you say you better get going, it’s almost his dinner time.

The elevator hums and dings on the third floor, a familiar sound, but each visit still feels uneasy and unknown. Turning the corner, you see him: a frail wisp of a body, a Buffalo Bill’s sweatshirt hanging off his bones. He’s facing the window, next to a potted fern, his blonde hair sprouting up over his heavy, electric wheelchair. You notice he’s strapped in now, like wearing a seatbelt. Was he always this small?

You spoon him lukewarm soup, and try to make small talk, except no one cares about the silence but you. It’s a one-sided conversation—it’s been this way for a while—and you tell him about your promotion at work and how the cherry blossoms are about to bloom. “Did you ever take your students to see them at the Tidal Basin, or was it too crowded? Thirty years of school trips as a chaperone, you must have seen them, right?” He refuses the last spoon of soup. His eyes are closing, his body slumped over to the right. He’s fading.

You’re desperate to tell him the truths that swirl in the silence of your sheets—the ones you whisper to your therapist, how some days sadness anchors you to your bed, or how, the very same year he moved into this horrible place, you somehow fell in love.

“Dad,” you hesitate. “I think I’ve met the man I’m going to marry.”

The words taste raw and sweet and you realize this is the first time you’ve dared to say them out loud. He’s the first to hear it—the first in on the secret. It’s thrilling and terrifying and you search his wrinkled, empty face but he says nothing.

“Dad, did you hear me?”

“Ok,” he murmurs, and motions for his pudding cup.

This time, instead of a smolder, it’s a dull ache. Grief is weird like that. You’ve been robbed of all the milestones and the tomorrows. Yet, you still don’t know which moment will fall flat like a withered balloon and which will kick you in your chest.

In that moment you hate everyone whose father received this news with a giant whoop and a beam and a “I’m so happy for you, Jenny.” Instead, you kiss his matted hair that faintly smells like cheap hand soap. You promise you’ll see him soon, then cry the entire seven-hour drive back home to Washington, D.C. The cherry blossoms are starting to bloom near the Jefferson Memorial and you see crowds of families smiling under the pink sea of petals.

How do you grieve moments you’ll never have?

My partner and I share a two-bedroom now—the kind that has too many magnets on the fridge and smells of palo santo and cooked garlic. His souvenir baseball cups crowd the kitchen shelves; my black dress hangs in the back of the closet, nestled between work blouses and old coats. It’s often where I find my cat curled up, fast asleep in its folds, as if even she knows it’s a place meant for quiet.

We’ve talked about rings, about what kind of wedding we’d want—something small, maybe in the Finger Lakes, in Upstate New York. Sometimes we say we’ll just elope. We laugh when we say it, but maybe it’s easier to imagine slipping away quietly than to picture the reception and the empty chair beside my mom.

Two years ago, I found The Dress online while mindlessly scrolling. Black, cinched at the waist, with a sheer leopard-print overlay that made it feel demure yet stylish. I didn’t need it, not really. But my breath caught in my chest when I realized I could wear it to my dad’s funeral. Is this something people do? Do they buy a dress for their dad’s funeral ahead of time? Most people reach for the ill-fitting black shift buried in the back of the closet, too stunned by grief to care. But I had time, I thought. I bought The Dress. I carried it with me from one home to the next.

The Dress has been worn just twice, once to my friend’s father’s funeral, the one with the roast lamb and the coconut cake. The one where the line wrapped around the building. It’s odd to think that my friend’s dad went from healthy to sick to buried, all while my father sat fading in his room at St. Ann’s. On occasion I still feel that singe in my gut when I think about how my friend’s dad got a love-filled fanfare while mine slips slowly away, half-forgotten.

Since my dad moved into the nursing home, I’ve run three 5Ks—the last one with my partner, breathing steady, by my side—and my doctor’s bill remains too high. Two springs of cherry blossoms have swept the sidewalks of D.C. Since his diagnosis, thirteen waves of pink petals have unfurled, blossomed, and drifted to the ground.

Hidden deep in my Notes app, I have two different drafts: one is the beginning of my wedding vows, the other is my father’s future eulogy. I write them both in fits, but never on the same day. Both are ahead of me, both waiting. Just hanging, like The Dress.

How can a heart be both broken and full?

About the author:

Jenny Phillips writes press releases by day and essays by night. A communications professional in the food world, she lives in Alexandria, VA with her partner and two cats. When she's not writing, she's escaping to her family cottage in Upstate New York or reading cookbooks like novels. This is her first published piece.

Thank you. You compel me to wonder what you mean and then surprise me with originality concerning the repetitive elements of normal lives. And the dress, oh man, that hit.