here's to summer (1994)

by Robert David Clark

I BOUGHT A BIKE THIS SUMMER. A blue Schwinn bike, one of those rugged-looking jobs with fat knobby tires and twenty-one gears.

I came to biking mostly by chance. Mike Magnuson is into the sport. He and I met in a writing workshop at Mankato State University last fall, eyeing each other like wary bears circling a salmon.

And one Sunday in April, I ride over to his apartment on a borrowed bike and catch him as he’s heading out for his daily ride.

“Hey, you wanna come with?” he says.

I look at his attire and nearly say no. Mike’s a fairly big guy, and with his yellow helmet, black T-shirt, and a pair of black Lycra biking shorts on, he looks more like a professional wrestler than a cyclist.

“Yeah, why not,” I say.

Mike throws his leg over a tired-looking turquoise mountain bike and says, “Then follow me.”

Only pride keeps me close to him while he leads me up one side and down the other of the La Sueur River Valley south of town. By the time we return to his apartment an hour or so later, my butt feels like I’ve been straddling a train rail, and my legs are on fire.

“That was fun,” I say and hope he’ll think my grimace is a smile.

“You should buy a bike,” he says. “We could do this all the time.”

That afternoon, I purchase the Schwinn.

When May ends and summer begins for real, we start to feel like there isn’t any distance we can’t ride. That’s when Mike starts talking about centuries. A hundred miles in one day. I do some quick calculations. Let’s see now, a hundred miles… thirteen miles an hour… seven times… carry the… “Oh, hell yes,” I say. “With a five-minute break, we can do it in seven-and-a-half hours, tops. We could pedal to Rochester and get prostate surgery while we’re at it.”

“Well, we need to do something,” he says. “We can’t keep riding around aimlessly. We need a goal.” He says goal like he’s rolling his mouth over a jawbreaker.

A few days later, we find our goal. We’re on the Sakatah Singing Hills Trail, a rail-to-trail that’s mostly gravel, taking a break on a picnic table next to Eagle Lake, Minnesota, when I see him staring up the trail.

“What are you lookin’ at?”

He says, “Faribault. How far is it?”

“At least forty miles,” I say and stare at the gravel path cutting through the beanfield to the east of us.

“We could do that,” he says, “couldn’t we? It’s flat. We could do eighty miles. Don’tcha think?”

I try grasping what eighty miles on a bike would be like. Eighty miles of constant riding is not something to be taken lightly, at least not at the pace we like to keep. I’ve been accused of lots of things, but intelligence isn’t one of them. “We can do it,” I say.

Plans are made. Our riding from here on will be with one goal in mind: our “assault on the Bault,” as it comes to be known. We vary our daily rides. Some days, we ride the trail as far as Madison Lake, twenty miles, racing each other in two-mile sprints. Other days, we pick a route with hills. We ride them all. Val Imm. Adams Street. Main Street. Both sides of Good Council. And the mother of all hills, Stadium. We ride out Monks Avenue on what we dub “The Ride of Death.” The valley out there has two hills that are nearly a mile each. This is where I learn that if you’re going to vomit, it’s easier to stop the bike rather than to attempt two things at once.

Nothing can stop us. We ride in the rain. We ride when the radio warns farmers to keep their livestock in the shade. We ride on days so windy that small craft advisories are issued for area lakes. But we are resolute. Faribault’s golden fleece looms on our minds.

On July 5th, we do a ride to Waterville and learn a valuable lesson. Don’t eat at Wallace’s Family Restaurant—ever. We should have known as much when a bored high-school girl places water glasses on our table and tells us the day’s special is roast beef or chow mien. “Help yourself,” she says and motions at the buffet table. “It’s all the same price.”

I go first and come back to our table. “Don’t get the chow mien,” I say.

The roast beef is of a texture and flavor I haven’t experienced since my army days, and this being Tuesday, I figure the corn in front of me hasn’t been yellow since Sunday. On the return trip, that same corn leads a charge through our digestive tracks. With each belch and fart, we conclude that we have endured a “Lunch Most Foul” and vow to carry only real “biking food” with us on Friday, August 5th, the day we’ve set for our ride to Faribault.

For the rest of July, we keep to our regimen, and though we ride a lot of different routes, our favorite destination seems to be that picnic table by Eagle Lake. White pelicans soar in circles above us while painted turtles sun themselves on half-submerged logs. On top of their houses, muskrats munch on bullrushes as carp roll below them on the surface. It’s a relaxing place, the kind given to conversations that have no urgency but seem so important all the same. At times, we tell outright lies, each of us knowing but having the courtesy not to call each other on it. But we always speak of writing. We describe scenes from the novels we’re working on, repeating dialogue our characters say to see how the lines sound.

Toward the end of the month, Mike hands me the final fifty pages of his novel. “Read it and tell me what you think,” he says. I do. And a few days later, we meet at his place. When he reads my two-sentence critique on the last page, his face turns red, and his head gives a jerk like I’ve thrown a punch. Here’s what I’ve written: It’s good. Now make it better.

We don’t speak for three days. On the fourth day, he calls me and says he’s thought about it and, after a few comments about my ancestry, says he can, and will, make it better.

August 3rd, two days before our assault, we meet to make final preparations. We decide to leave at six a.m. on Friday in order to get a jump on any wind that might come later. Mike claims his worst fear is to come limping back from Faribault in the dark like a couple of stray dogs.

“No way,” I shout. “We can do twenty miles on belligerence alone. Quit worrying.”

But the idea of our failing to do this thing in a respectable time scares me, too. I know Magnuson will be inconsolable. He’ll moan about the indignity of it for weeks and might be driven to such a level of despair that he’ll deliberately ride his bike into a tree—or worse. On Thursday, I buy a saddle pouch, tube patch kit, and a tire pump. Our bikes’ components are degreased, cleaned, and oiled. Tires pumped to maximum pressure. All is in order.

The morning of the 5th arrives with cool sunshine and a clear sky that will last the day. At exactly 6:05, we are riding through a damp mist rising from the canopy of trees at the beginning of the trail, and—except for one event—the trip to Faribault passes quickly.

On the east side of Waterville, a golden retriever sunning himself by the trail suddenly wakes to find what must appear to him strange deer passing. He charges Mike, barking, head lowered, trying to draw a bead on moving feet and calves. Mike stares ahead with a look of resignation, almost as if he welcomes the attack. Something to show the grandkids someday. See this here? Got that from a Rottweiler on a ride in ’94. At the last moment, the retriever turns and trots back to his yard, secure in the knowledge that what goes up the trail eventually must come down.

We skirt Morristown, and about four miles outside of Faribault, the trail turns to asphalt once more. At 9:25, we reach the Dairy Queen marking Faribault’s end of the trail. Mike is in a jaunty mood. “We’ll do a century in under eight hours next summer,” he says.

For twenty minutes, we rest on Dairy Queen’s tables, eating Fig Newtons, fruit, and trail mix. After some brief stretching, we saddle up and head for home.

I suppose we’ve been too proud of ourselves to notice, but the wind has picked up during our layover. Now the wind blows in our faces and seems to be getting stronger. In no time, we learn that the wind’s speed is about the same as our own, and we lean into our handlebars and get on with the struggle. This is going to be work.

Around mile fifty-five, I realize the hallucinations of the last three miles aren’t all bad. At least the time is passing quickly. A pain, an ache really, develops in my left kneecap, then my right. Legs so strong on the way over now begin to tighten.

I look to Mike for inspiration.

“I wanna puke,” he says without looking at me.

End of conversation.

The scenery is gone now, lost in the periphery of the trail before us. From a distance, slight inclines take on humongous proportions and seem to rise forever. The bandanas under our helmets drip sweat on to our sunglasses like bugs hitting a windshield. Even the traffic noise on the highway to the south of us is gone. Now the only sound is that of the chains and gears and tires crunching gravel and a blonde cape buffalo snorting on the bike next to me.

We approach Waterville, and sure enough, right where we’ve left him, the golden retriever waits, and he’s brought a friend. Every Far Side cartoon I’ve ever seen flashes before me. I imagine their conversation: Hey, Sparky. Ya wanna have some fun later? I see them in leather jackets, leaning into a streetlight, eyeing two rubes from out of town, cigarettes dangling from the sides of their mouths, but there isn’t anything for us to do but ride on. When we are fifty yards away, they begin to bark. I watch their tails. The retriever’s is up and wagging. His friend’s tail, however, lies down like his ears. He’s also stopped barking. Now he’s smiling. Bad sign.

Sometimes, it’s not so awful to be insane. I start singing. Sinatra’s been crooning to me from somewhere beneath my helmet for the last few miles, and I join in. I have nothing to lose, so Frank and I roll into our version of “The Summer Wind” as we ride past. This seems to catch the dogs off guard, and by the time they’ve figured out how to handle this new turn of events, Mike and I are standing on our pedals with a renewed vigor that only comes from adrenaline-charged fear.

Time seems to lose its meaning when you’ve lost touch with reality. You fail to note the sense of its passing. Everything seems locked in a single moment that surrounds you like a bubble.

On the west side of Elysian, a swarm of deerflies enter that bubble, falling into the draft behind our backs. They bite at will and stay with us for several miles. I ride just to the left of Mike’s rear wheel, studying the curve of his back while flies chew through his shirt. I swat one from my neck and imagine how it might feel to stab a large knife into that arched back or maybe run a broom handle through his front spokes, sending him down into a crashing heap to be eaten by the hungry insects.

Halfway to Madison Lake and I have the strange sensation that I’ve been on this bike forever. It isn’t fun anymore.

“Tell me a story,” I say to him.

“I don’t know any,” he says.

“Well,” I say, “I’ve got one for you. For the last few miles, I’ve been thinking of murdering you and dragging your body off into the weeds.”

“Do it quickly,” he says, but I notice he slows a little and keeps me in front of him the rest of the way to Madison Lake.

We keep riding, knowing that if we stop now, we may never get moving again. But then suddenly, a mile out of Madison, a change comes over us. In a few short miles, we will be at our spot by Eagle Lake. We begin to realize this thing has an end. The trail seems friendlier, the wind not so much of a factor. Eagle Lake comes and goes, and with the last of it, the gravel trail. Asphalt, black and smooth, lies before us as we cross the highway, and our tires touch paved trail again.

For nearly eighty miles, we’ve had the trail to ourselves, but now we see people ahead in the distance. Closer now, we see two young women on rollerblades, kicking from side to side like hockey players going for a loose puck. They smile and say hello as we pass. When they are out of earshot, Mike, with his flair for the dramatic, says, “Thank you, Sisters. You’ve done more than you’ll ever know.”

The tree-shaded canopy blocks the wind. We shift our chains to the big ring. We lean back on our saddles and enjoy a spin we haven’t known since leaving that morning. We suddenly feel renewed and strong. The miles behind us less painful as we savor our accomplishment.

After loading our bikes into my truck, we sit for a moment on the end gate and raise our water bottles for a silent toast.

“Think we coulda done a century today,” Mike says. “We coulda. Couldn’t we? We coulda done it if we had more trail, right?”

“Hey, buddy,” I say. “We coulda rode forever.”

So here’s to summer. Here’s to white pelicans and yellow-headed blackbirds. To dogs that charged but didn’t bite. Here’s to wildflowers that grew along the path to Duck Lake as if they knew we were coming. To cars that gave us the right of way. And to those that didn’t. Here’s to young women on rollerblades with lovely legs and smiles who made us feel stronger. Here’s to summer, 1994, and the way things were, not how they should have been. And yes, here’s to friendship, and life, and that sense of immediacy placed on them both by the swift passage of time.

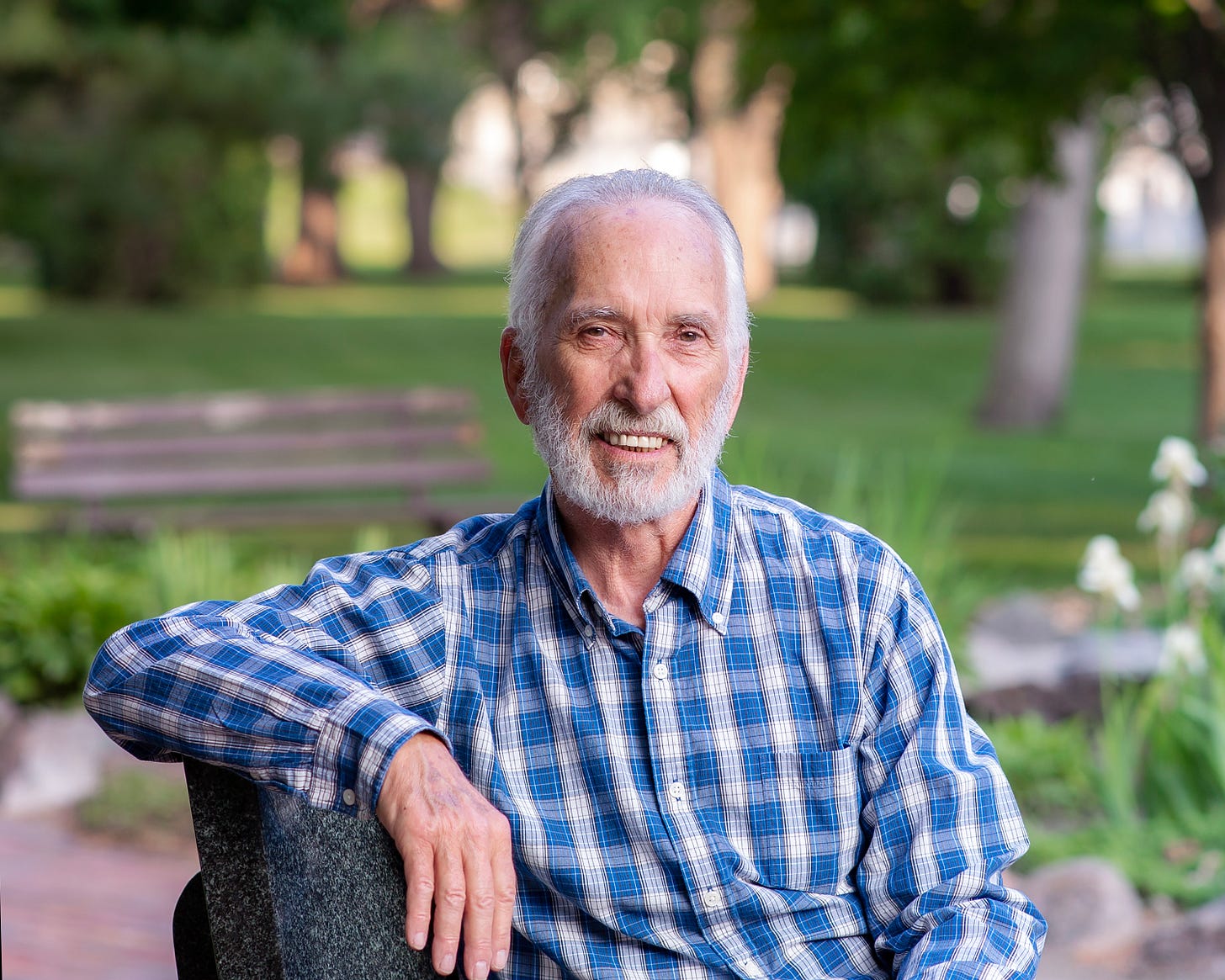

About the author:

Robert David Clark (November 4, 1948 ~ August 24, 2025) is author of the novel Flowers of the Dinh Ba Forest. He was born and raised in Bondurant, Iowa, and in 1968, he was drafted into the army and served a tour in Vietnam. He was wounded in battle, returned to duty, and was awarded a Purple Heart. After the war, he moved to Mankato, Minnesota, and worked for forty years at Mankato Citizens Telephone Company. He also studied Creative Writing at Minnesota State University at Mankato. He is the recipient of a Robert C. Wright Award and an Associated Writing Programs award for fiction, and his shorter work has appeared in Indiana Review, The Highground Magazine, Minnesota River Review, and other publications. He wrote “Here’s to Summer” thirty-one years ago, in September of 1994. sneaker wave magazine is grateful to his daughters for permission to publish this story.

This story makes me wanna bike. It also makes me want to have a friend as good and as true as Bob.

Who fed your bike addiction, who criticized your writing without giving you specific comments, who revealed your lummox-ism to anyone who would listen, who saw through your tough guy persona.

Jeez, we’re all worse for not having him around. We’re all gonna die, and his silenced voice is a reminder.

He was good.