endless khakis

by Luke Thompson

BY THE TIME I REACHED EIGHTH GRADE, the Catholic Church had rendered me fashionably illiterate. I had spent too much of my childhood wearing school uniforms from the only diocese-approved vendor in Portland, Dennis Uniforms, founded in 1920: “Outfitter of required apparel for private, parochial & public schools, plus shoes & backpacks.”

Dennis Uniforms resided in a building tucked away between the gray underbellies of the Hawthorn and Madison Street overpasses, a purgatory of stiff air and dim fluorescents to which we and our parents were remanded once a year as penance for the summer growth spurts. In the heat of that last week of August, my brother and I would wander through the racks of uniforms, perusing the styles, as if this time the inventory would present something new. Classmates would float through now and then, but the months of summer and the presence of our parents made too many layers of unfamiliarity. Consequently, we were all but strangers in Dennis Uniforms.

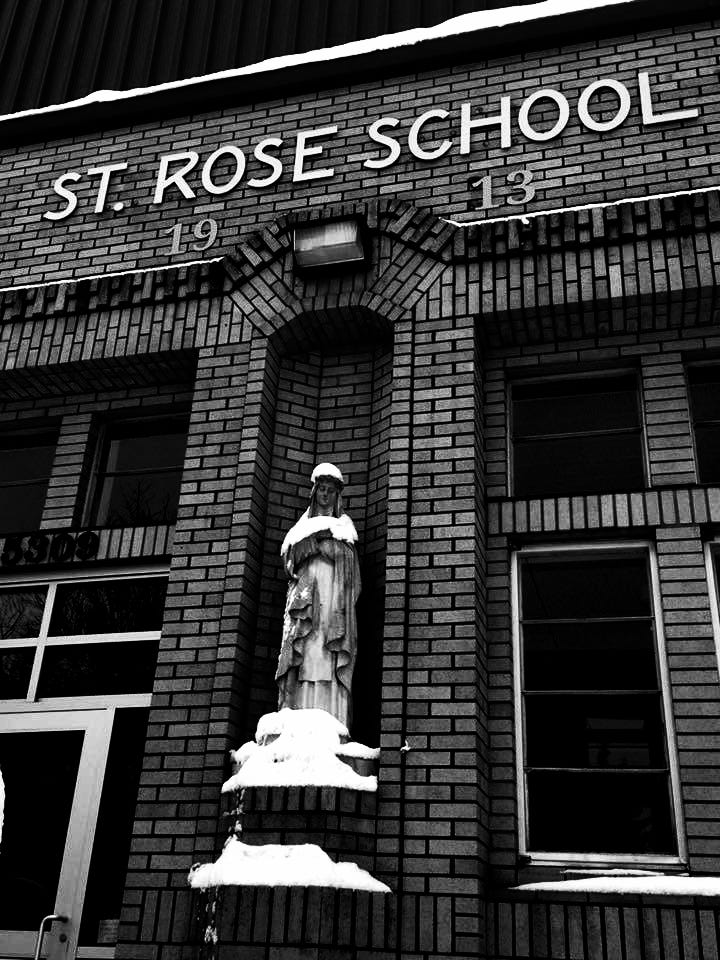

Ours were navy polo shirts and khakis—endless khakis, two dresser drawers stuffed with khakis. They had cheap inseams and were always too tight around the waist, and they bore the logo of St. Rose School—a silver cross with a rose at its center—stitched over the heart, where they always itched. The school upheld these articles of clothing as a bastion against secular trends, as a solution to mockery, and as a preventative measure against fashion disasters and coyly defined “distractions.” A closet full of spares was across the hall from the front office, and every so often a girl would be sent down to it, the length of her pleated and plaid skirt found wanting.

Dress codes were strict, and yet the manner of enforcement was always under renovation. In seventh grade, St. Rose School instituted RUP points—Respect, Uniform, Punctuality. If you were late or had misbehaved or had worn socks with logos on them, your whole class lost RUP. It showed up on your report card and everything.

Free Dress Days were our reward for accomplishments, for meeting fundraiser goals, for ending the trimester with the least lost RUP out of every grade, for the completion of another successful Christmas program.

In the case of the fundraisers, I never held much hope. Every pledge drive and Jog-a-athon was a head-to-head between the Ameses and the Radigans, the dueling dynasties, each of which had a kid in every grade except mine, and the winner was routinely determined by which pool of relatives was feeling more generous that time around.

The upper grades were constantly hemorrhaging RUP, as we were the least well-behaved, and naturally, the Christmas program yielded the most egalitarian fruits. After the final song, which was always “Oh Happy Day,” sung by every kid in the school, Principal Asbury would take to the podium, from whence all Gospels were proclaimed. Though it was a longstanding ritual, she could always make it seem like our reward would be a surprise. She would say, with feigned reluctance, “I guess that since our Christmas program went so well this year, every one of our students has earned a day of free dress.” Our response was rapturous! But I wonder if, on the inside, most of my peers felt how I felt: paralyzed by sudden choice, compelled to make a statement but unable to imagine what that would even look like, afraid to enter into a nascent realm of failures for which we could be judged.

Still, more often than not, I donned my uniform.

St. Rose had many rituals—Christmas programs once a year, Confession every six months, Mass every Wednesday. Some were grade-specific: first graders took First Communion, third graders were Confirmed, and in their final semester, eighth graders were inclined to attend a seminar.

The school had scheduled a seminar one Wednesday in early February 2017, and my eighth-grade class—reduced to ten after years of attrition—was instructed to wear formal attire. Boys needed slacks, a button-up, and a tie, and girls needed skirts, flats, and cardigans—the kind of attire my Catholic classmates would have grown up wearing to Easter Vigils and Christmas Masses. Navy shirts and khakis would not suffice when God was watching more closely.

This was daunting news for me. No one in my family was Catholic. I was at a Catholic school because there weren’t a ton of other choices. The last teacher I’d had at my neighborhood’s public elementary school had informed my parents that it was necessary to enroll me in special ed, which my parents did not like the sound of. Uniforms and weekly mass at Catholic school seemed like acceptable trade-offs. My mom advised me to think of it as a “cultural exchange.”

As a result, we had not gone clothes-shopping anywhere but Dennis Uniforms since I was eleven, so I owned very little that was not either a navy shirt or one of the endless khakis. Puberty had further complicated matters by leaving me stranded at an awkward and inconvenient six-foot-one, standing in front of my closet, appraising my limited resources. I ended up going with a dark blue polyester button-up with a black tie, golden corduroys, and my dad’s old belt and shoes.

When I entered the kitchen at breakfast, filled with simultaneous embarrassment and pride at my outfit, my well-meaning father turned from washing dishes in the sink and, not realizing that my shirt was one size too small, said, “You’ve slimmed up!”

The seminar was the only thing on the schedule for eighth graders that day, and when we filed into a dingy upstairs room of the adjacent church where Mrs. Czuba normally tried to teach music, I had a sinking feeling when I saw that the chairs, usually arranged in a circle, now faced the blackboard in ranks. There were far more seats than there were eighth graders, and so we sat ourselves haphazardly. I don’t think any of us wanted to be sitting too close when the lecture started.

The Lifesavers Retreat, as it was called, was relatively straightforward as far as Catholic sexuality rhetoric is concerned. The whole thing was administered by a woman who could not have been much older than twenty-two, and let me tell you, I’m twenty-two years old now—for whatever that’s worth—and I don’t think I could give a purity talk to eighth graders with any more grace than she did. I remember her stockings and heels and pencil skirt and the gray sweatshirts of the two high school girls who served as her henchwomen. I presume they were getting service hours. Their leader talked for the duration of the lecture, which had the timbre of three hours but was probably ninety minutes. It became clear that at fourteen, we had ventured dangerously far into adolescence, and it was now necessary for the grown-ups to intervene. All of us were called to abstinence, an edict of purity shunted from one generation to the next, like world peace. The importance of modesty, which none of us had forgotten, was nonetheless re-articulated. Most of the time was spent admonishing the baleful menace of Planned Parenthood, which was apparently orchestrating a campaign of abortion at once malicious and unfeeling.

But toward the middle of the retreat, there came one moment that made me sit up straighter. The young woman in the pencil skirt claimed that the Holy Spirit was created via perpetual intercourse between God the Father and God the Son. It was a theological truism that, over my eight years spent in the Catholic school system, I never heard repeated.

The conviction with which she said this was surreal, as if I could go to the catechism in the church office downstairs, flip to the relevant page, and there it would be, next to the section on Transubstantiation.

“When the Father and the Son have sex,” she said.

That is all I remember of that sentence. Perhaps my mind went pinging off into the void. Perhaps I was genuinely too tapped-out by then to react with anything beyond muted acceptance.

Toward the conclusion of the Retreat, we were each given a goody bag, the contents of which were uninteresting, except for a one-to-one scale plastic figurine of a sixteen-week-old fetus. Two of my classmates, Sawyer and Andrew, thought this was the funniest thing they’d ever seen, and they hid their fetuses in the disused drainpipe next to the door that led from the echo chamber to the courtyard. I put my goody bag with its plastic fetus in my locker, and when I graduated, I did not retrieve it. Perhaps someone threw it away, never knowing the irony of what they’d done.

After that, we arrived at 7:30 AM every day to stand on the cold concrete of the parking lot while the slow procession of cars would empty their contents of children in ones and twos and sometimes fives. We organized them into rows based on grade level, waiting for Mrs. Penwell to blow her whistle from the top of the steps, at which point the rows would unravel into a meandering line that streamed into the dour brick building.

At 2:50 PM, we would leave our cloister on the second floor, descend the black iron fire escape to the parking lot, and take up our posts while cars inched past and retrieved their charges.

On Good Friday, we got up on the altar and silently acted out the stations of the cross in front of the whole school. When we had gone to rehearse the Thirteenth Station—“Jesus’ body is taken down from the cross”—our khaki-clad Jesus got really embarrassed about being held in the arms of Mary, played by one of the three girls in the class.

Every few weeks, we were visited by emissaries of the Catholic high schools, with whom all the middle schools in the archdiocese had a standing arrangement. They brought merchandise and pamphlets and slideshow presentations full of smiling students doing homework and were indistinguishable apart from their colors—red and gold for Central, red and blue for La Salle, blue and white for Valley Catholic, green for Jesuit. That we would attend a Catholic high school was a foregone conclusion. Our teachers had made sure to routinely remind us that, “an A at a public school is as good as a C at a Catholic school,” and so I enrolled for La Salle Catholic College Preparatory for that fall.

On our last day of school, we ran the length of the school building, from rear entrance to front, past lines of the younger grades, who applauded and high-fived us and probably didn’t know half of our names. At the graduation mass, Father Matt warned those three girls against allowing people to define them by “any one trait,” while my mother averted her face from the other parents, barely containing her laughter.

Halfway through my sophomore year of high school, I was still finding khakis. I’d been bouncing between parents twice a week since sixth grade and had grown accustomed to keeping all my clothes in a duffel bag. As a result, dresser drawers would sit closed for months and then open to reveal neat stacks of khakis much in need of fresh air and a new life. Had the pants still fit, I may even have been desperate enough to wear them. A few of the navy shirts stuck around as well, wilting in the far corners of my closet. Those were relics from fifth and sixth grade that still sported the old logo of Archbishop Howard School, the name of which had been changed to Saint Rose due to the good archbishop’s involvement in church cover-ups. However, he had also co-founded my high school, and within its walls, his quiet veneration continued. Pictures of him hung in the chapel, illuminated by soft lights and accompanied by little bronze plaques. When I would sneak in during class to play the grand piano that was left over from the days when the chapel was the choir room, I would pass beneath the black and white photos of Archbishop Edward Howard breaking ground in 1966.

Why I ended up hacking my way through two Catholic schools between 2013 and 2021 had very little to do with faith. My family is an evangelical mishmash, and sometime prior to my fifth-grade year, I had developed the conspiratorial assumption that the Catholics had something to do with the death of Christ. My opinion of the Roman church was not improved by spending most of a decade under their tutelage.

In fifth grade, I asked Father Matt why the Catholics pray to saints. He answered by telling me to go read the Bible, which didn’t alleviate my feeling that if we must pray, we may as well cut out the middleman.

In eleventh grade, a visiting monsignor, whilst devising his homily for the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, thought it prudent to talk about how “the love of Jesus” put an end to the Aztec practice of human sacrifice. When a group of seniors subsequently penned an open letter reiterating that actually it was genocide and it would be nice if the monsignor acknowledged it as such, he threatened to sue us all for defamation.

I am not Catholic. And yet. That way has found me in the backroads off of Highway 26, clutching the steering wheel and praying the rosary to stop myself from hyperventilating. It has found me in a parking lot in Queen Anne, berating the waxing moon as if it were the open face of God. In quiet moments, 7:30 on Christmas morning, walking to my mom’s apartment, groggy at a time which used to be no trouble at all—the Lord’s Prayer. The hymns we sang every Wednesday of middle school were always too high or too low for my adolescent voice, and yet I sang. I still sing. If someone asked me to recall one out of the thousand names of God that I would elect as the truest, I would refuse. If someone asked me if the impetus of the gospel, the very Resurrection itself, actually happened, I would not know how to answer. Still, I feel that awe I had when a sparrow flew into the church during the silent prayer, while we knelt and craned our necks to watch it flutter around the ceiling. Still, I sing.

During the final moments of the Lifesavers Retreat, the leader’s two detached teenage assistants passed out little squares of cardstock, onto which we were invited to sign our names—a symbol of our commitment to ourselves and to God that we would not have sexual relations before marriage. A few of us signed, and I have forgotten who they were. But I was not among them. And though abandonment of that edict would not be resolved for another three winters and a spring, when it eventually was, amidst global catastrophe, in the back seat of a 1999 Subaru Legacy on the side of a residential street in Eastmoreland in broad daylight, the education administered by that edict’s adherents finally worked its will, and in the end, neither of us were brave enough to take off our pants.

Which, in my case, were khakis.

About the author:

Luke Thompson grew up in Northeast Portland, Oregon. He is currently finishing his undergraduate degree in music at Pacific University, where he has interned with the Masters of Fine Arts in Writing Program. He trains as a singer, stage actor, and pianist.