conrad and the circles

by William Bartlett

CONRAD LIVED IN A NEW HIGH-RISE in the far West Village, twenty minutes from my place in SoHo. Our meeting was scheduled for Sunday afternoon, so, briefcase in hand, I set off to his apartment. Since his building had no doorman, Conrad buzzed me up. He was a dark-haired, bulky man in his early thirties, twice my age, and he led me into an immense, virtually empty apartment with floor-to-ceiling windows. The light streamed in to illuminate a sparsely furnished living room with more boxes than furniture.

I had no idea what his rent was, but I was certain it was many times the $80 a month I paid for my illegal sublet on Prince Street, right above Vesuvio Bakery, in a six-story tenement building mostly occupied by elderly Italian couples who had raised families in 324-square-foot apartments with a bathtub in the kitchen and a water closet in the corner. In 1978, it was still possible to score a housing deal in New York City. My roommate and I gave a guy named David Berkowitz $160 a month, and he sent $32.50 to the landlord, forging the name of a long-ago-deceased lady whose name was on the lease. A win for everyone (except the landlord).

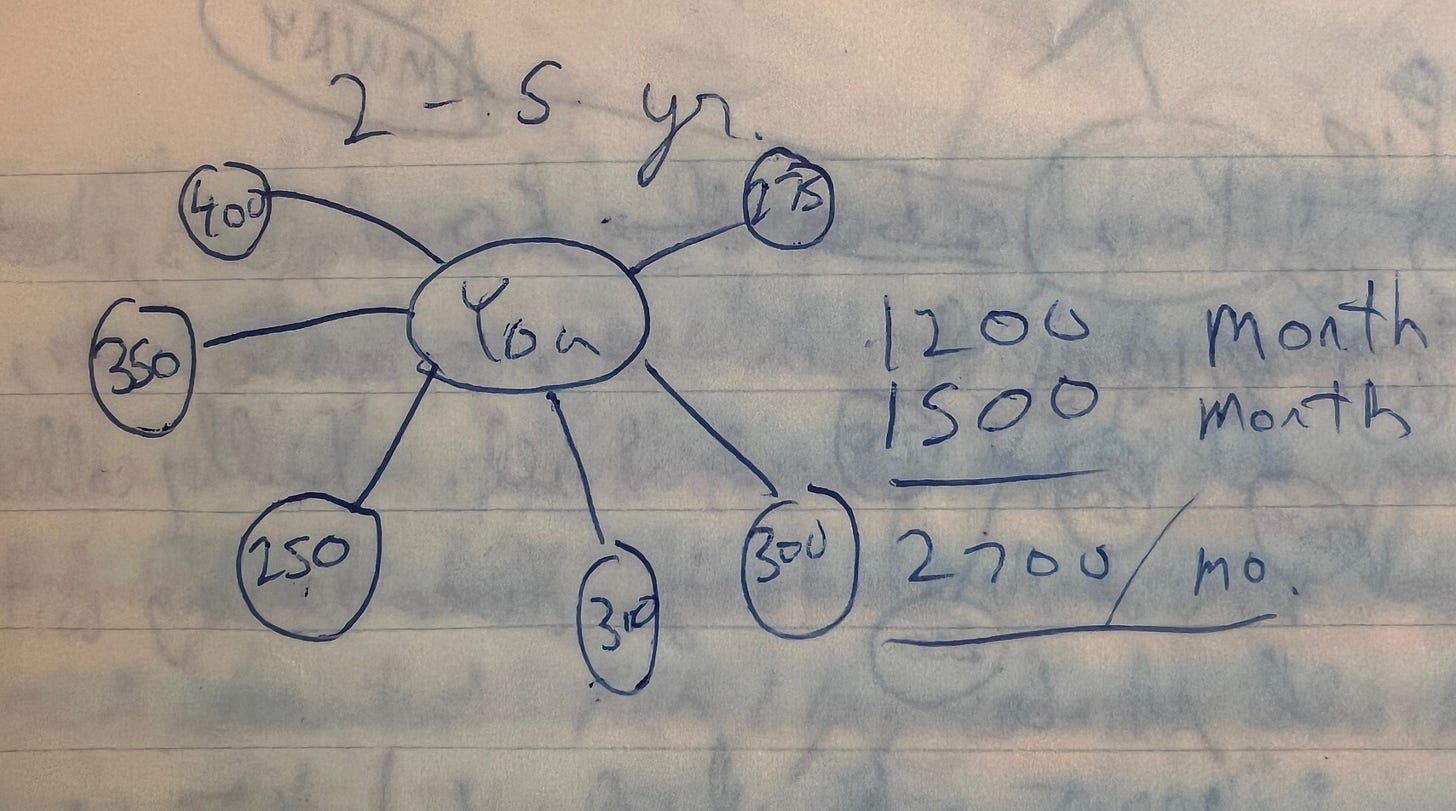

When I was comfortably seated on a white leather sofa, I put my vinyl folder on a glass-topped coffee table and opened it to reveal a pad of unlined white paper. “I’m going to tell you about a business opportunity that can lead you to wealth beyond your dreams,” I said. With my blue felt marker, I drew a large circle. “This is you.” I drew a medium-sized circle above that and connected them with a line. “This is me, your sponsor.” I added six small circles around the Conrad circle. “These are the people you introduce to the business.” Then I started putting numbers in the small circles. “If each of the people you sponsor generates $100 of sales in a month …”

Conrad politely listened to me reciting the script the way my parents had taught me. My goal was to “show the plan” at least twice a week. If I did that, I would be successful. Even if most of my prospects turned down the opportunity, some would sign up, and my organization would grow. It was inevitable. At least, that’s what my mom and dad had been told. I’d been on my own in New York City for only a few months and had not yet shown the plan to more than a dozen people. No one had signed up yet, but I wasn’t doing it twice a week, either.

I had met Conrad on a bench in Washington Square Park, where he told me he’d just arrived in New York from Indonesia. I find it hard to talk to strangers, so I’m pretty sure he initiated our conversation. Once we were talking, I remembered my twice-a-week goal, steeled myself, and blurted out, “Would you like to hear about a business opportunity?” We made the date, with me scribbling down his address in my daily planner.

After adding up the numbers in the small circles, I was starting the part about the 30 percent of Business Volume, which is where the real money kicks in. That’s when Conrad stood up, casually walked around the coffee table, and sat beside me on the couch. Close to me, almost touching. My presentation stopped midsentence when his hand slowly crept to my thigh, where it paused, an inch from my crotch. I grabbed the folder and bolted. Conrad missed out on an important part of the business plan.

And that was the end of my career as a teenage Amway distributor in New York City.

I didn’t tell my parents back in Florida about Conrad and my close call. And I didn’t tell them I was quitting the business, giving up on the multilevel marketing scheme. But I know I quit, because in my journal I stopped drawing the Amway doodles: pages filled with the circles and connecting lines that showed the path to riches I was supposedly pursuing. My self-flagellations over not meeting my twice-a-week goal stopped as well.

Until my meeting with Conrad, I had thought I could do both: become a professional dancer and “get rich quick,” as I put it in my journal. Dancing was what had brought me to New York City. I had moved there from Orlando after winning a spot as a scholarship student at the Joffrey Ballet School. I managed to sell some laundry soap and vitamins to Mrs. D, the school’s administrator, and a six-pack of “food bars” to Miss Lister, one of the teachers, but that was the extent of my sales. My profits were miniscule. I was a long way from riches. And I knew I needed to focus on my training, because if I were to succeed as a professional dancer, it would take everything I had. My pirouettes and double tours were excellent, and I had good elevation, but my feet didn’t point, my back was stiff, and I needed to refine my arms and presentation. Miss Baylis told me I needed to command her attention, take risks, let myself go. Mr. Joffrey himself put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Deeper and fuller.” He taught us that every movement a dancer makes needs to convey intention, meaning, and emotion. That’s what professional dancers did, and I knew I had a lot of work ahead of me to achieve that quality of movement. Being distracted by “showing the plan” wouldn’t help.

My parents had become Amway distributors a few years earlier, when I was in high school. My mother was tired of struggling. Dad was a dreamer, not a doer, full of big and impractical ideas that went nowhere. “There are oranges all around us,” he would say, as he spread his Dundee Orange Marmalade on his burnt toast. “We should start a marmalade factory!”

Meanwhile, his paving and grading company was failing. Mom, a violist in the Florida Symphony who taught piano and violin on the side, had limited earnings potential. She was very active in the American Federation of Musicians Local 389, and I still remember how proud she was for winning a contract that boosted pay from $180 to $200 a week, for the twenty-six weeks or so of employment that the symphony offered each year. Still, even back in the seventies, that wasn’t a lot of money, and she could only teach so many students. She had come to accept that Dad would never 1) work for anyone else, or 2) run his own business successfully, but she thought if she took the lead, Amway might just be the path to solvency, if not riches. They were driven by desperation, motivated less by hope than by a potential escape from hopelessness.

I don’t know how my parents met their sponsors, Don and Mary. What was more important was who sponsored them. That was Tony and Liz. They were the “upline Emeralds,” in Amway speak, on their way to becoming “Diamonds.” Every few months, Tony and Liz would drive their Cadillac from their South Carolina McMansion to Florida to inspire Don and Mary and their downline distributors—including my parents. Tony was a five-foot-six Italian with working-class roots who was now rich, and he made sure everyone knew it. He would pace around our living room in his baby-blue leisure suit and platform shoes, waving his arms and telling my parents to “never let them steal your dream,” and warning them to banish any negativity, which he called “stinkin’ thinkin’.” Liz was the model wife, adoring and subservient, perfectly dressed and coiffed, laden with giant jewelry, her platinum hair piled high on her head.

My parents were both educated, literate, with master’s degrees. Episcopalians. Readers of books. They played bridge. My mom was a classical musician, for God’s sake. I don’t think they had ever waved their arms. Tony and Liz were not their people.

But they were millionaires, and Mom and Dad were broke.

Along the side wall of my parents’ garage was box after box of Amway products. Everything you would need for a home, for a dozen homes: cases of SA8, Dish Drops, and Zoom. Satinique for your hair and Glister for your teeth. And the bestselling LOC (liquid organic cleaner), which I still have a bottle of, nearly fifty years later. Along with plenty of Nutralite Double X vitamins, which came in translucent green plastic containers with a month’s supply and only cost a dollar a day.

Occupying a different wall, just right of the door to the kitchen: four linear feet of shelving filled with copies of the Amway bible, The Possible Dream, and at least that much space stacked with dozens upon dozens of cassette tapes. Inspirational tapes to put in your car and listen to on your way to show the plan. Or to play on your portable Sony cassette player while cooking dinner. In the corner was the aluminum easel, colored markers, and large pads of paper that my parents would put in the trunk of their Honda Civic on the way to an appointment, or set up in the living room when they had people over.

I desperately wanted my parents to have financial security. But I didn’t want them to be anything like Tony and Liz. I was repulsed by their country music, their lack of sophistication, their ignorance (I assumed) of the things my parents valued, like Mozart, the Book of Common Prayer, Scotch, and Agatha Christie. Could my parents pull off the riches part without getting infected by the repulsive part?

No, they couldn’t. I recently learned how truly hopeless their quest was, when I stumbled across a documentary about Amway that explained how the scheme could lead to riches. News flash: It wasn’t by selling soap and vitamins. The percentage of revenue scooped off by those at the top of the pyramid wasn’t enough to support the absurdly ostentatious lifestyles of people like Tony and Liz, with their diamond rings, their Cadillac, and their fur coats, which Liz would keep on even in the Florida heat.

There was one approach alone that would enable this lifestyle. It became known as the “tools cult,” and it referred to the sales of not just cassette tapes but books, seminars, and conferences: BSM, or “business support materials.” All paid for out of pocket by people like my parents, and all with the same message: just believe hard enough and you will succeed! And if you’re not succeeding, you’re not believing hard enough, and you need to attend more seminars and order more tapes. Cut out a photo of your dream car and your dream house and your dream vacation home and tape it to your fridge, look hard at that every morning, while drinking your coffee and listening to a tape. No stinkin’ thinkin’!

My parents had cassettes delivered every week, for them and the handful of people they sponsored. Endless variations of the same theme about positive thinking and visualizing success. The cassettes cost my parents $5 each and cost Tony and Liz 60 cents, if that. Unlike a box of soap, where Tony and Liz would get a small percentage of the retail price, with the cassette tape, they would pocket nearly the entire amount. Multiply that by thousands each week for a few years, add on the hundreds of thousands in annual profits from Charlotte’s “Free Enterprise Day” rally (which in 1980 featured Ronald Reagan as the keynote speaker) and other events, and, yes, you too could buy the pink Cadillac of your dreams and have plenty left for the gaudy diamond rings and fur coats.

Why couldn’t my parents see that? Why couldn’t they do the math? They were blinded by desperation. What was I blinded by? I wasn’t blinded. I was just a kid. And my eyes were focused on something else.

I had stopped “showing the plan.” I wanted to dance, to perform, and to get paid for it. Why? In my journal, my seventeen-year-old self answered that very question: “Because I like to dance. Because I want to be able to do something as beautifully as Helgi Tomasson and Anthony Dowell, and I want to thrill and move people like they do.” There was nothing more enchanting than ballet, and I would do anything to be part of it, even if it meant constructing a rope contraption to hang from the underside of my homemade loft bed, which I’d strap my feet into in order to stretch my legs into a split. I was up for any torture that would help me earn a spot in a professional ballet troupe. The clock was ticking. Most female ballet dancers had begun their careers by eighteen. Men had a bit more time, since usually they started their training later, but not that much more.

Nearly all the scholarship kids at the Joffrey School had to economize, but I outdid them all. In the late 1970s, the Wednesday edition of the New York Post included an ad from the General Nutrition Center with coupons for a yogurt, a bag of chips, and an apple juice, 10 cents each. There was a trash bin on the corner of Eighth Street near Bigelow Chemists, and another at Ninth just before Balducci’s. It wasn’t hard to pull six discarded newspapers from those bins when I passed them on my morning walk to the studio and tear out the coupons, and there was a GNC conveniently located down one block and across Sixth Avenue from the Joffrey. At the end of the week, I’d make the entry in the little red diary I used as my financial ledger: “Lunches: 30 cents x 6: $1.80.”

I was luckier than many of my friends, since I was a trust fund baby. A very poor version of one though. I owed that to my Great-Aunt Martha, back in Sanford, Florida, who adored the idea of my becoming a dancer. Although she herself had very little, she promised to send me $200 a month, as long as I sent letters, keeping her updated on my progress. The checks would come until my nineteenth birthday. Then, I’d be on my own, and selling a box of soap to Mrs. D wasn’t going to cover the rent.

I started eking out a modest living through freelance gigs. Mrs. D would get frequent calls from regional ballet companies around the country looking for young male dancers, and she’d dole out the opportunities to her favorites. The pay was modest but the experience invaluable. I had a one-off performance of the pas de deux from La Fille Mal Gardée in New Rochelle. A weekend of Coppelias in Charlotte. A month of Nutcrackers in Wichita, partnering the portly daughter of the ballet school’s owner. A Tribute to Pavlova in Pasadena. Plus, a recurring role earning $5 a night as the Joffrey Ballet’s “flower boy” for their performances at New York City Center, where I’d walk on stage in my brown polyester suit to hand the ballerina a bouquet during the curtain calls. Then, when I was twenty, I hit the bigtime. I was offered a contract with American Ballet Theater’s apprentice company, ABT II. A touring company of eight men and eight women, all in their teens or early twenties, we traveled the world, performing in dozens of cities in the U.S. and abroad. I was off and running, no, dancing, and the circles and connecting lines of Amway were left far behind.

Five years after joining ABT II, and a career that included stints with troupes both in the United States and abroad, I retired from performing and enrolled in college back in Orlando. My parents were still following the dream. They never did “go diamond.” For them, as for so many others, Amway did nothing but cost them money they never had, their dream not crystalizing into the diamond they had hoped for but decaying into the heavy blackness of disappointment and regret. Did they ever realize that it was all a scam? Or did they just think they weren’t good enough to be successful? I never asked them. All I know is they still had lots of cassette tapes.

About the author:

William Bartlett is an avid cyclist and retired corporate speechwriter in New Jersey. During a long career, he published many articles and op-eds, but nothing with his name on it, except a history book in 2019 called NBC and 30 Rock: A View from Inside. He enjoys cooking and taking bikepacking trips with friends. His business website is still live, for some reason, at williamvbartlett.com. This is his first published personal essay.

Dancing, the art and work of it, is demonstrably worth it, especially in retrospect. The contrast between you creating an improve-your-split rig and the inventory in your parents’ garage makes my heart ache a little. We can’t begrudge folks figuring out how to make a living and wanting to make art (including the pudgy young dance you partnered). Amway was in my family too. My mother bought cleaning products from Uncle Turkey, so named by our blunt Amish relatives because of his unfortunate nose. Thank you for this piece. And it’s never too late to make art.

I'm someone for whom Amway is in the realm of the mythic, this kind of proto-MLM that started it all...it's so fascinating to hear about what it was like to be involved, and to see people in all these different stages of success and not-quite-making-it.