che cazzo fai

by Rachel Lincoln Sarnoff

BY THE TIME I turn fourteen in Florence, I can hold a conversation in Italian, and my father shouts “Buongiorno!” at every opportunity, regardless of where the sun is in the sky. We live in a spacious, modern apartment with tile floors and iron-barred balconies. He grins in the amber Tuscan light—the first real smile I’ve seen for months.

But in the tiny space of the cambio, his voice is too loud. “Five hundred lire to the dollar, Rachel! Do you know what this means?”

I calculate the exchange rate in terms of a Coke—here, about twenty-five cents. “It’s good, Dad.”

I finger the rainbow-colored bills, as small as Monopoly money. My five-dollar weekly allowance, which five months ago in Los Angeles got me a matinee movie ticket and maybe an ice cream cone, is now extravagant. I hope my father will let me keep it. He fans the banknotes like a full house. “We’ll live like kings!”

He wants to spend his newfound wealth on a Fiat Cinquecento, red, with a tan leather interior, mahogany dashboard, and a gearshift striated with gold. The car is a tiny box with rounded corners—as fast as a sports car and small enough that four men can pick it up and move it out of a parking spot, if necessary. But he can’t get the permit to buy the car. Gaetano, my father’s patron at the university, fills him in: Here in Italy, you grease the wheels. He slips the dealer a few bills and the car is ours.

We drive to Spello and spend a night at Gaetano’s ancestral home. The house is like an archaeological dig: a twentieth-century second story on top of an eighteenth-century first, with a basement dug during the Etruscan period of the second century. My father buys a demijohn of Sangiovese—a giant green glass bottle that stands as tall as my hip—and arranges to have it delivered to our apartment the following week. Gaetano insists that once you open a demijohn it has to be bottled immediately or the wine will go off, and he sends us home with a few empty jugs.

When the demijohn arrives, I suck on the plastic siphon to get the tap started and work with my father to transfer the tube from bottle to bottle, trying not to spill a precious drop of the wine he insists is the finest in Italy. But there are fifteen gallons in the demijohn, and we are far short of the seventy-five bottles we need to contain it. We empty water bottles and rinse out tomato jars, even fill up a few empty shampoo bottles. For weeks, purple-stained containers line our blue-tiled hallway. My father brings wine to his colleagues and students, but without another adult to help drink them, the bottles stand like sentries in the hall. Soon, the apartment smells sour and musky, like the underside of a cask. This is when my father’s late-night calls begin. A few weeks later, Karin, his ex-girlfriend, moves in with us.

At first, it’s a thrill to have Karin back in our lives. Each morning, I hop on the bus to the American School, and my father drives to work at the university. Karin walks to the mercato, where she fills mesh bags full of boxed pasta, produce, and panna di cucina—a pre-packaged white sauce that is the basis for most of the creamy recipes I love. We eat blood oranges, their flesh impossibly sweet and striated with red stains, and penne sautéed with finocchio, a local fennel that tastes like licorice. Karin pours a glass of wine for my father and, following tradition, one cut with carbonated water for me. Even diluted, it makes my head spin.

Karin focuses her attention on me, and in that rose-colored light, I bloom. I mimic the deliberate way she purses her lips while applying frosted lipstick and the teasing sway of her walk. I copy how she sits at dinner: back straight and elbows in, fork in her left hand and knife in her right. Karin blows her hair out into a chestnut bob, which matches the straight and shiny texture of my short crop, and we both retain a California tan. We stroll through the golden afternoon light of the San Lorenzo Market. Finger the buttery leather goods and smile at the shopkeepers. I imagine they think we’re mother and daughter. She brushes the hair out of my eyes and rests her palm on my cheek. Her hand is as soft as velvet.

I take the seat across from Karin at a table in the corner caffé. The lemon-yellow tablecloth flutters against our legs as the waiter approaches wearing a long white apron that falls past his knees. I flaunt my newfound linguistic ability and order the artichoke salad for both of us. It is our favorite—a bitter, nearly raw concoction finished with fresh lemon and olive oil that leaves a sweet tang on my tongue.

“Perfetto,” Karin says breathily. Perfect. “E aqua, per favore.”

“Fizzante o piatto?” the waiter asks. Karin nods at me to decide whether we will have bubbly or flat water.

“Con gassata, grazie,” I answer. I roll the r across my tongue. Bubbly.

“Bravissima, Rachele,” Karin says. Her r still at the front of her mouth, Americanized. “Your accent is perfect.”

“Grazie.” Maybe if I am good enough at this, she will stay.

We speed through the Italian countryside. Fields of sunflowers bloom on either side of the road, chocolate faces shyly tilted away from the light. Karin is the passenger, and I’m cupped into the tiny bucket back seat. I crouch into the slope of the leather, angle my legs, and hold my knees in my hands.

My father drives without speaking. He shifts into the downgrades and barely touches the brake on the turns. The Fiat rumbles when it idles and accelerates like a whippet from a gate. I love the feeling of weightlessness when the transmission hovers between gears, the subtle play between shift and acceleration, the thrust when the clutch releases and the car surges forward.

But on a sharp curve, Karin reaches to grab the handle above the passenger-side window. She turns her head and sucks air through her teeth. My father pulls over and turns off the engine. The sign points left to Firenze.

“You’re going to have to, you know,” he says.

I wince. They’ve had this argument before.

“To what?” Karin’s white knuckles, the skin stretched taut between them.

“Drive. I can’t leave you alone with Rachel if you can’t drive the car.”

“Oh, Ken, I can’t.“

“Of course, you can. You drive at home, don’t you? You’re going to move halfway across the world and not experience the joys of the autostrada?”

Minutes later, my father is in the passenger seat watching Karin check the rear view, then the side mirror, then the rear again. Finally, she inches the car into the intersection and flicks on the blinker. There is nobody approaching, yet still Karin hesitates. She purses her glistening lips. Drivers pull up behind us.

“Che cazzo fai?” a man yells.

This loosely translates to “What the hell are you doing?”

“Let’s go, Karin,” my father says.

“We are going.” Her teeth clench.

I sink lower in my seat and wish he would just leave her alone.

“Vaffanculo!” The driver of a convertible red Alfa squeals around us and through the intersection. This word serves as the universal “fuck you” in Italy.

“Come on, Kar,” my father says. “Punch it!”

Karin yanks the emergency brake and turns off the car and slams open the door and places one foot on the pavement. “Fuck you, Ken!” she says. “I’ll take the bus.”

She steps onto the asphalt, cream linen T-shirt snug over tight flared jeans, hair gleaming red in the sun, chin up and spine arched. The drivers who have pulled up behind us stop honking and rubberneck. Her hips sway in time with her steps. She strides confidently down the middle of the empty oncoming lane, literally stopping traffic.

“Belissima!” The driver in the yellow truck kisses his fingers as he screeches around our car to turn the corner. The others follow, wolf-whistling.

At the sidewalk, Karin turns and flicks my father her middle finger, then struts towards the bus stop. He sighs and steps out of the passenger door. Slams it behind him and walks around to the driver’s seat. I stay in the back. We drive home alone.

My school’s end-of-year formal is held on a Friday in a two-story trattoria with heavy velvet drapes and circular tables clustered on a black-and-white checkered floor in front of an empty stage. Afterward, I’ve planned to spend the night with my friend Adriane; my father and Karin will pick me up in the morning for a weekend in Pompeii, a five-hour drive from Florence. Adriane is fifteen and from Texas; she has long legs, green eyes, and short brown hair shaved at the back and curling over her forehead. She teaches me the electric slide, lines my eyes with thick liner like Cleopatra, and loans me a black shift dress that clings to my doughy curves.

At the formal, Adriane and I share a two-top. The teenage wine dilution rule is not enforced (or the waiter is being paid by the bottle), and I nod yes over and over when I am asked if I would like altro vino. Then I stumble to the bathroom and vomit all over my beautiful gray boots.

My father shakes me awake in Adriane’s bathroom. His eyes are dark, and the tub is cold. My neck is cramped at a weird angle. I sit up, recognize Adriane’s gray Longhorns T-shirt and white leggings but can’t remember putting them on. The room smells like sick, but there is no sign of it, only an empty metal trashcan that looks recently scrubbed. I don’t remember anything after climbing into the bathtub, covered in barf. I taste the bittersweet remnants of it in the pockets between my cheeks and gums, but the rest of me is clean.

“You ready?” my father says.

“My head hurts.” I wince and shudder.

The headache occupies the space between my eyebrows and pain radiates through my jaw. I picture it pinging back and forth inside my head like a scene from Tron, the spasm vibrating and twanging against the end of each circuit.

“I’ll bet,” he says. “Let’s go.”

“Can’t I stay here?” I gag and swallow it back down.

“No, you can’t.” There is no arguing with that voice.

In the front seat, Karin grips the handle, jaw tight. I climb into the back and my father hands me a plastic bag. He starts the engine and we head out of the city. The tires squeal around the corners and bile rises in my throat. We leave behind the cement block apartment buildings of our neighborhood and enter the lush, green countryside, where clusters of pine trees stretch towards the impossibly blue sky. Rectangular houses, stuccoed the color of goldenrod, old enough to have been built when this road carried carriages rather than cars. It’s picturesque, but the mallet pounding in my head forces my eyes closed. More than the physical pain is the emotional. I have failed. I did not stay in control. I am not a good girl. I am bad. I sink low in the seat. I curl myself around the empty hole below my heart and close my eyes. I am too disappointed in myself to cry.

I wake to find the car parked in a large gravel lot; a grass field and some low buildings are about a hundred yards away. My headache is gone—as are my father and Karin. Being alone doesn’t frighten me. I sip from a warm glass bottle of Acqua Panna. How long have I been asleep? One hour, two? My stomach cramps, but the liquid stays down. I step into bright sunlight, squinting. No other cars or people, just a uniformed guard in the metal booth, clashing with the crumbling blond stone and faded terracotta brick behind it. I flash my student ID, and he nods me in.

The streets are oversized slabs of gray stone edged with flat rocks that catch the heels of my boots. Buildings cluster in a semi-circle around a thin smokestack tower, surrounded by a low, crumbling wall. Three white-washed columns hold a slab of marble that must once have been the frontispiece of a roof. I know from my history class that two thousand years ago Mount Vesuvius had erupted without warning and choked the citizens of Pompeii to death where they stood. It left their bodies perfectly preserved in ash. But I am not prepared for this:

A man arches his spine, screaming.

A dog writhes on the stone.

A mother curls on her side and wraps her arms around a child.

The sun feels filtered through a giant magnifying glass. Beams of light sear my scalp, and sweat soaks through the back of my thin t-shirt. Each step stirs a small cloud of dust and I inhale microscopic fragments of the bodies buried underneath my feet. Where are Karin and my father—did they drive off and leave me behind? My heart thumps hard in my chest. I am alone, walking on graves. My stomach lurches and cramps. And then I feel it, the slow seeping between my legs.

I had gotten my period before. The first time, I was eleven and sliding down a hill of ivy behind the school bus stop at the Hilton. I went into the hotel to pee and discovered the rusty, sticky mess. I hadn’t prepared—hadn’t even had the talk with anyone—but I knew about menstruation from Judy Blume books. I was so proud, punching in the numbers to my father’s office on the pay phone. He raced to pick me up and took me home to shower while he rushed out to buy supplies and a bouquet of flowers that he put in a vase in my room. He only knew about the tampons his girlfriends stashed under the sink; one time, I explained that I couldn’t use them, and he had to drive all the way back to get pads. But bleeding isn’t a regular occurrence, not yet.

I crumple against the stone wall and draw my knees up to my chest and clench the muscles of my thighs, but the stain blooms through my white leggings. The air is still. I taste salt on my lips. There are no birds, no butterflies—no sound except my jagged breath. I want Karin. I need her to take me away from this dead city. To stroke my hair and tell me what to do.

It feels like hours before she finds me. Tears track my cheeks, but she doesn’t wipe them away. She yanks me up and towards the porta-potties next to the parking lot, where a bus belches out tourists in neon-colored tracksuits. I slide in front so she will shield me from view.

“Stop it.” She pulls me back to her side.

“But they’ll see.” I shimmy back over.

“Nobody cares.” Her cold fingers manacle my wrist.

The tourists chatter and flow around us, oblivious. Karin holds open the porta-potty door, and the medicinal smell of disinfectant mixed with shit makes me gag.

“Here.” She pulls a super-sized tampon from her purse.

“But I don’t know how!”

“That’s all I have.” Her brown eyes shine like flint. “Figure it out.”

I won’t understand until later how a person like my father can make you want to hurt someone else. I just know that Karin has turned on me, and it has something to do with the blood on my hands—proof that I am a woman, acting like a child. I close the door and hold my breath, wince as I shove in the tampon. When I step out, I am different. Accept his sweater and tie it around my waist. Sit in the back seat without speaking. Watch the sunset fade to black during the five-hour drive back to Florence.

I stop believing in mothering. I stop believing in mothers altogether.

A week later, when Karin packs her bags and flies home to Los Angeles, I have one less to deal with. It wouldn’t have worked, anyway—having Karin as my mother. I am now a woman, and women, I know from my father, disappoint. They are expendable. Push one down and another pops up in her place. You don’t try to be good, if you are a woman. You never live up to expectations—so why try? Better to be the bad girl. Better to live for the rush of endorphins you get from a bottle or a body. Better to leave first, if you can. Like my mother and my father, although he won’t admit it, crying into his glass. You can leave a person while she’s still in the room, even asleep at your side. My father knows that—perhaps my mother taught him. And that it is better to be needed than to need. But I never can quite master that last part. There is always that empty, abandoned space inside of me. I vow to fill it with music and wine and scarves and coffee and boys with soft curls and strong hands.

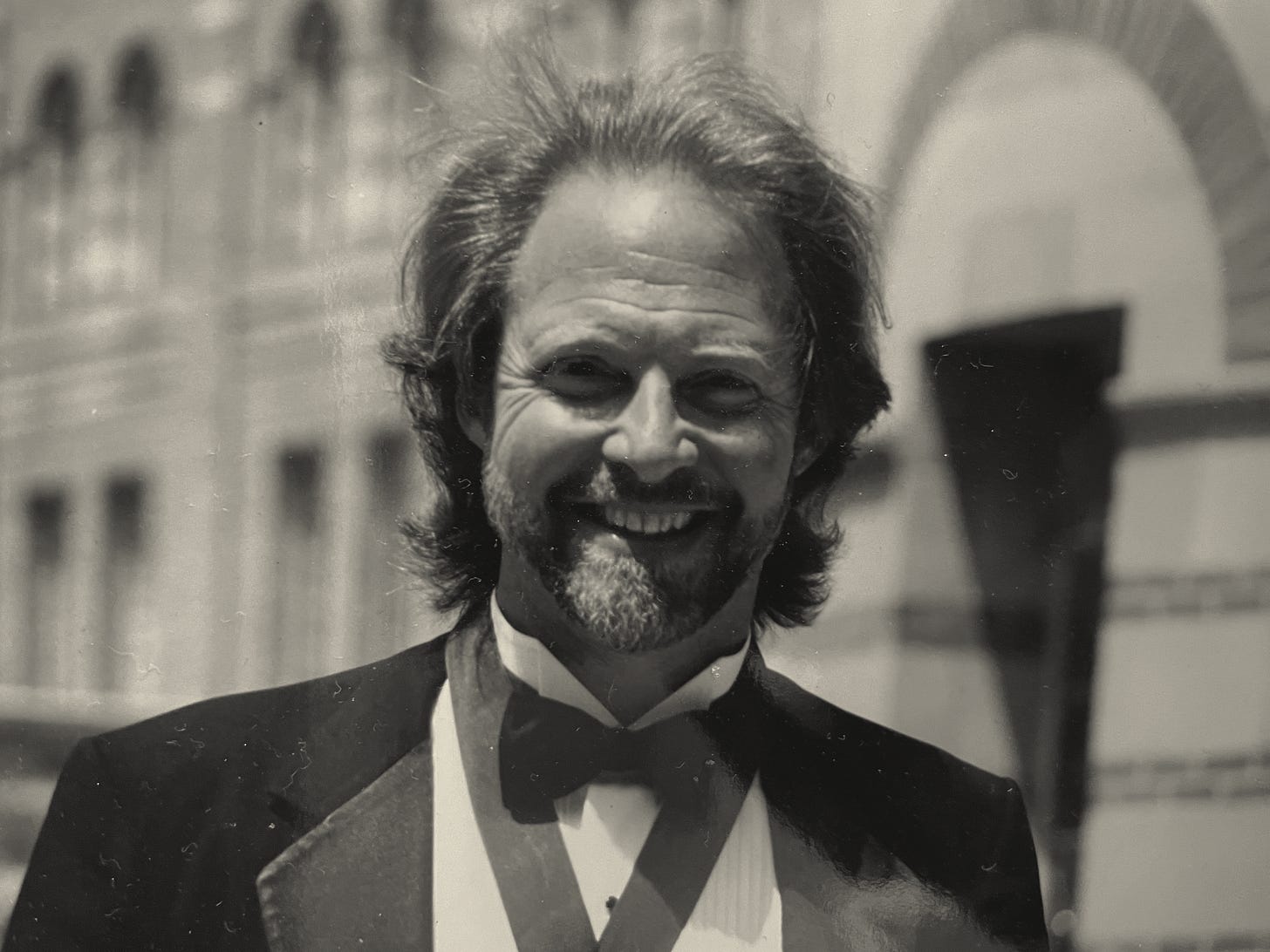

About the author:

Rachel Lincoln Sarnoff has recently published work in Northwest Review, Hippocampus, and the Washington Post. She holds an MFA in fiction from Pacific University and an MA in journalism from USC. Rachel’s career as an environmentalist informs her fiction, creative nonfiction, and Good Newsletter (since 2008). She lectures at UC Santa Barbara, mentors young writers through 826LA, and is an active member of the Authors Guild and the Women’s Fiction Writers Association. Rachel is currently querying her first novel. RachelLincolnSarnoff.Substack.com

“It is better to be needed than to need.” Wow! Thank you for all of this.

Rachel! This is so, so good. Thank you.