boys of the 70s

by C.J. Janovy

IT’S OBVIOUS, NOW, how the boys of the 1970s claimed for themselves everything that was so alluring about girls. Maybe that’s why I thought I liked them.

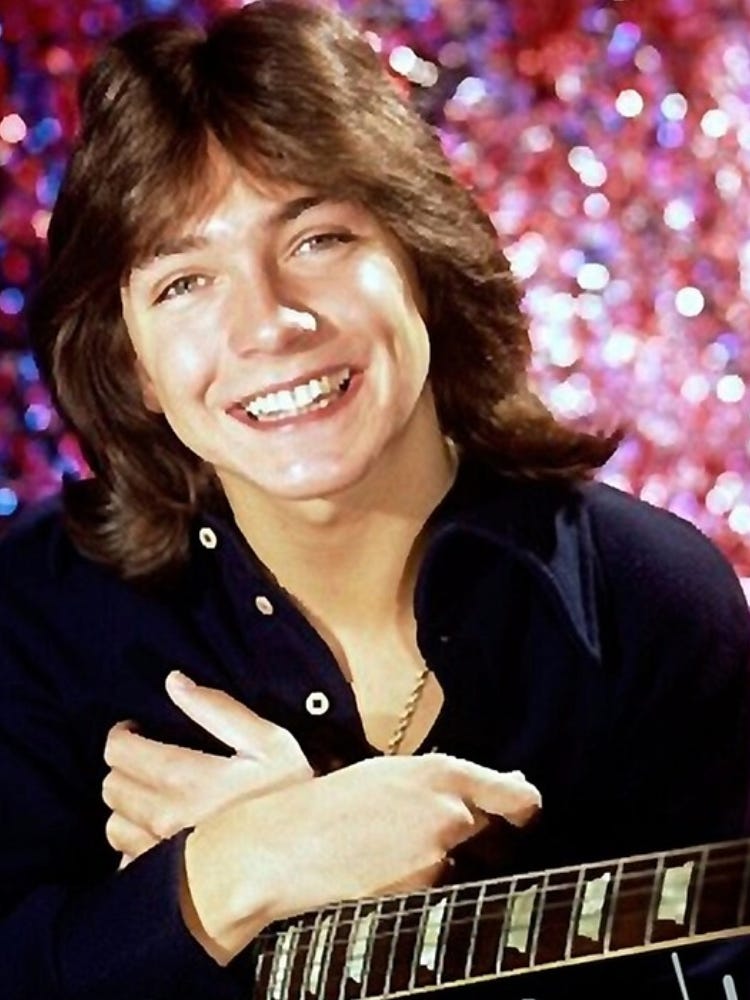

I was just as boy-crazy as any other girl whose fifth and sixth grades coincided with David Cassidy’s run in The Partridge Family. His piercing eyes sparkled under his silky brunette shag as he smiled beguilingly from the poster on my wall, brightening my bedroom like sunshine through the window. As guitar-playing Keith Partridge, he dramatically balanced the role of teenage rebel in the family band with his responsibilities as the eldest son of a widowed mother with four other kids. The Partridge Family’s biggest hit was “I Think I Love You,” and the feeling was mutual.

When David Cassidy was the main attraction at the Nebraska State Fair, my dad caved to my pleading and bought cheap tickets far up on the metal grandstand benches. From there, I could see that David Cassidy’s pants and shirt were not the same shade of white. “His outfit’s wrinkled,” my dad added when he took his turn with the binoculars. I noticed that, too, but couldn’t acknowledge the feeling that maybe David didn’t really care enough about us. It was my first concert, and I wasn’t ready to be disappointed by rock stars.

David Cassidy died of alcoholism at age 67 in November 2017. As I watched the internet overflow with beautiful photos from his time in teen magazines, I was floored to realize how, at his peak in 1972, David Cassidy looked like a teenage girl. I hadn’t thought of him in decades. And by then I knew that my earliest TV crush had not been on David Cassidy but on Barbara Feldon, the tall, sultry, intelligent and problem-solving Agent 99 to the idiotic spy played by Don Adams on “Get Smart,” which ended its five-year TV run in 1970, just as “The Partridge Family” began. Maybe I didn’t understand my feelings back then because no one made a poster of Agent 99.

My first kiss was with a fifth-grade boy, hiding in the bushes on our walk home from school, after he’d written “Will you go with me” on a tiny piece of paper, wadded it up, and thrown it at me in class. Our lone kiss in the bushes sparked no desire for another one, and neither of us really knew what we were supposed to do after declaring that we were going with each other. The relationship didn’t last long.

I made out with a boy at church one Wednesday night during junior high youth group, lights out in one of the fellowship rooms where the soft couch was meant for comfort during Bible studies. He produced an alarming amount of slobber, which did nothing to smooth the sharp early whiskers on his upper lip. Youth group was better for smoking my first joint with a couple of other kids in a stand of pine trees across the street. As we sauntered woozily back into the building, I felt the brick walls, decorated with crayoned Sunday-school artwork, shift ever so slightly before we settled in for pizza and preaching.

In 10th grade, when kids from various junior highs mixed for the first time at one big high school, a legendarily cute guy who’d gone to a different junior high inexplicably liked me. This caught the attention of the popular girls from various schools who’d all found each other and coalesced into a single organism of cheerleaders and chorus stars. These girls cautiously accepted me into their lunchroom circle. But this guy’s lip was also spiky. I understood why boys this age were so proud of their young whiskers, but didn’t they care how it might feel to a girl who just wanted soft lips? Plus he was self-absorbed and boring, so I broke up with him. “You’re crazy,” one of the lunchroom girls told me, implying I’d never get another boyfriend that good again.

I proceeded to prove her wrong. As a member of the girls’ swim team I was obligated to be a fan of the boys’ team, and over the winter season I managed to catch the interest of a smooth-skinned, clean-shaven blond diver, a shy Adonis who’d bought a red Trans Am with money from his grocery-sacking job. Dating a senior elevated my status, even among his straw-haired, chlorine-smelling teammates who lurked like asshole big brothers. On our first date, to a Friday night basketball game, I decided to dress up a little and wore cream-colored corduroy Levi’s with a sweater instead of my usual blue jeans and flannel shirt. “Lose the white cords,” one of the teammates scoffed at me. Adonis didn’t seem to mind whatever I wore, and for the rest of that year the two of us were that most annoying of high school creatures, the conjoined couple who walked the halls with hands in each other’s back pockets. On Saturday nights I told my parents we were going to the movies but we went instead to the basement at his house. On the couch in front of the TV, we made out with the buzzy intensity of two teenagers genuinely in love, though neither one of us ventured inside the other’s pants because I lived in the fearful legacy of 7th grade health class films and told him we’d never do anything that could get me pregnant, a rule he respected. I should have risked it, because Adonis was the only boy I ever loved.

But I was just a sophomore, and after that year, he was heading to the university. I knew that my parents, who liked him a lot—I was always home by midnight, after all—would never let me go out with a college guy. I figured he’d fall for some sorority girl anyway. I pre-empted fights with my parents and the heartache of him dumping me by breaking up with him early in the summer after he graduated. He wrote me a letter about how he didn’t understand. I never wrote back.

The first boy who did get into my pants was a kid who sat next to me in swing band during the fall semester of my junior year. He was a year older, muscular and not too much of a band geek, but outside of our time in the saxophone section, I’d never paid any attention to him. One day, the two of us were practicing in the music teacher’s office down the hall from the band room, fluorescent lights on, hard metal chairs, music stands in front of us. “Let me finger you,” he said. Not exactly knowing what he meant, I allowed him to reach over and unbutton my jeans, shove his hand in the tight space between my legs and wriggle a stinging finger inside me. The room smelled hot with male energy. I’d barely buttoned up my pants before the band teacher opened the door and looked surprised. I figured he was happy to see us practicing, but years later I’d wonder: Did he suspect what had happened just before he walked in? Did we act strangely? Did he catch that whiff of humid boy hormones? I vaguely understood I’d been violated in some way, but was mostly just glad we didn’t get sent to anyone’s office. The horn player and I resumed not paying attention to each other.

Eventually I decided to just go ahead and lose my virginity. Like getting a driver’s license or enrolling in Advanced Placement English, it was something I needed to take care of. Unwilling to risk any gossip, I determined this would have to involve a boy from a different high school, someone unknown by everyone else in my world. So one Saturday night when I’d heard about a rival high school’s party, I followed directions to a stranger’s back yard on the other side of town and stood around watching the crowd. Near the keg was a kid with a cool new haircut like we were starting to see on British rockers, short in front and longer in back. Led Zeppelin was cranking on speakers someone had dragged outside, and I liked the way this kid nodded his head. A few weeks later we went on a date, which was not to a restaurant or movie but to the empty apartment of his older friend, all thick carpet and wood paneling, dust and dim light. He spent a lot of time sorting seeds and stems, oblivious to me, before we took a couple of bong hits and went to the bedroom. What I remember most was the feeling of a sizable zit on the guy’s back. What I don’t remember is his name.

The truth was, by the time I lost my virginity to a boy with zero feelings before, during or after, I was already in love with a woman at my high school and she with me, each of us maintaining two parallel lives. I dated boys but snuck into dark classrooms to make out with her. I wrote letters to her built around Top 40 love songs even though that meant it was always a man’s voice on the radio telling her how I felt. We avoided getting caught but we knew people could tell from our lingering together too long in the hallways that something was off, like a paragraph in the middle of a narrative suggesting a whole different story but going no further.

By senior year I managed regular dates with another well-built athlete, a wrestler who, unlike Adonis from sophomore year, was so uninteresting that I risked no danger of liking him. His admirable body, meanwhile, lent me the appearance of fitting in at least around the edges of the jocks and cheerleaders.

When it was time for prom, my mother sewed me a peach-colored knee-length strapless cotton dress and the wrestler I’d been pretending to date arrived at our house wearing a cream-colored tux with silver trim, corsage in hand. My dad took pictures. Then, with my parents believing we were going to dinner at the steakhouse where everyone went before prom, we drove instead to the flashy mid-century motor lodge on the city’s main drag.

Up the concrete stairs, in a room on the second floor, three similarly dressed couples waited for us, FM rock playing on a boombox and a bathtub filled with ice and beer. Next to the sink was a bottle of champagne and a row of plastic flutes. On the mirror, in red lipstick, one of the girls had scrawled “Dust in the Wind,” that year’s prom theme, acknowledging the fleetingness of high school through the title of the (only) Top 10 hit by Kansas. We cracked open beers and high-fived the wrestler who had procured these primo party arrangements through his fake ID, a driver’s license for someone named Tracy O’Neal. Who the hell was Tracy O’Neal, we wanted to know, laughing and toasting Tracy O’Neal in our grown-up clothes—until the door blew open and in walked a pissed-off older man we didn’t recognize. Following him were a couple of cops. The older man was apparently the motel manager, all puffed up and red in the face, gripping his enormous ring of keys like a service weapon.

“Who’s Tracy O’Neal?” asked one of the cops.

I steadied myself against the dresser and tried to calculate my consequences. One cop was now interrogating my date. The manager surveyed the bathroom, fuming over the lipstick on the mirror as if it had broken the glass. As our situation became clearer, I began to understand the manager’s point of view. When he hadn’t been going out with me (and I hadn’t been going out with him), the wrestler had been using Tracy O’Neal’s driver’s license to rent rooms at this motel all winter, leaving them trashed and skipping out on the bill.

I imagined my parents getting a call from the police station and determined I could not allow that to happen. I approached the second cop and nodded in the direction of the wrestler.

The cop leaned in, hands on his belt, listening.

“I can’t,” I stammered, genuinely trying to figure out what to say. “I’m on student council.”

His actual words were: “There, there. Don’t smear your makeup.”

The cops didn’t care that they’d busted a roomful of underage drinkers. They only wanted Tracy O’Neal for the damage and the unpaid room charges. My cop’s partner wrote the wrestler a summons to appear in court and gave us a short speech that ended with instructions to enjoy our evening. Tragically, we’d have to leave our bathtub full of unopened beer. But we made it to the prom, in a decorated ballroom downtown, where a band played the same songs by the Doobie Brothers, Journey, Bob Seger, and Rod Stewart that we’d been dancing to in our school cafeteria on Friday nights for the past three years. In our official photo from that night, the wrestler and I are smiling, him in his cream-colored tux and me in my home-made peach dress, radiant under a flowered gazebo with “Dust in the Wind” spelled out in glittery letters.

A Kansas song more apt for my own life at the moment would have been “Carry On My Wayward Son,” but that would have required me to imagine a different gender for the titular character. I was used to doing that for the love songs I quoted in letters to my secret girlfriend, transposing or eliding genders and awkwardly twisting Top 40 sentiments to fit our narrative, but neither of us liked Kansas enough to bother with that one.

Besides the prom night photo, there was other proof that I’d led a typical high school existence. One evening toward the end of the year, I walked a few blocks from my house to a palatial home on “the lake”—a few acres of private shallow mud pond encircled by fancy suburban homes with docks for motor boats and pontoons, where the richest kids in my neighborhood water-skied in tight circles. People had noticed something inexplicably weird going on with me, but I’d maintained enough status to secure an invitation to a yearbook signing party. All of the jock boys and popular girls were there, drinking beer and eating Doritos, cranking music as the late-afternoon sun glimmered off the brown water. “Love ya,” some of them wrote in my book. “We had a few good times, didn’t we?” “You really know how to make the year go fast!” “Best of luck in your future life of crime!”

The girl who lived in the house was named Marianne. She and I hadn’t been close friends, but she’d been nice to me over the years and I was glad to be at her party. It felt so normal, lounging on lawn chairs with all of these kids I’d been growing up with, some in their prime and all of us on the edge of adulthood. I could see Marianne was happy to have all of us there with her, and she lit up when we all heard a familiar sparkle of acoustic guitar coming over the speakers. The singer of Boston’s “More Than a Feeling” was experiencing something vague but we could all relate to it anyway (the song had peaked on Billboard’s Hot 100 at No. 5 in a few years earlier and, in the decades to come, would rotate heavily on the yet-to-be-imagined radio format known as Classic Rock). When it came to the end of the first chorus, Marianne threw her arms in the air and sang along: “I see my Marianne walking away.”

Marianne had a song, one with forceful riffs and pounding rhythms, long-haired singers whose facial hair and falsettos were undeniably masculine. Her song was easy. The music told her story, and she didn’t have to translate lyrics from another gender. I was happy for her. But it was time for me to leave.

About the author:

C.J. Janovy is a veteran journalist with deep roots in the American Midwest, now living in Portugal and writing the Queer Elder Expat column on Substack. Her book No Place Like Home: Lessons in Activism from LGBT Kansas won the 2019 Stubbendieck Great Plains Distinguished Book Prize, was nominated for a Lambda Literary Award in LGBTQ nonfiction and was named a Kansas Notable Book. She has led newsrooms as director of content at Kansas City’s NPR affiliate and as editor of the city’s alt-weekly; she was also founding opinion editor at Kansas Reflector. Her articles, essays and fiction have been published by Switchyard, Catapult, NPR, New Letters, Ms., the New York Times and elsewhere. Check out her website.

One of my favorite little easter eggs in this piece is how many cream-colored outfits there are! Ah, the 70s. What a portrait.

So real. And do I detect a cliffhanger? I hope that was a cliffhanger suggesting a part 2 to come…