a photograph

by Owólabi Aboyade

FOR AS LONG AS I CAN REMEMBER, I wanted to have a son and name him after my younger brother Lee.

When we were young and alive together in Detroit of the 1980s, we called Lee “Leroy” from time to time. Uncle Ricky, my mother’s baby brother, started the nickname. I think we got a kick out of it because Leroy was, to our young ears, an old Southern name that mothers no longer give their kids. Our parents were born in Jim Crow’s Georgia and Mississippi and moved north to the Blackest city in the country, and we siblings were used to hearing dialects transported across place and memory. Still, we didn’t yet understand how Uncle Ricky was blessing my brother. Remember: “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown, the baddest man in the whole damn town.” I think that’s how the song went. I don’t know—it was before my time.

Leroi, my son, was named after my brother Lee. My ex-wife added this other empowerment, donning him “LeRoi,” French for “the king.” So my son’s name is simultaneously ancestral, Southern, an inside joke, an inheritance (my father’s full name is Large Lee Copeland; his brothers include Tommy Lee and James Lee), a translation, a compromise, and on top of all this, a title to command respect from the white world if he should find himself there.

Sometimes, when my tongue is too tired for two syllables, I call him “Le,” which sounds like “Lee.”

I just dropped Le off with his mom. I’m back home on the east side of Detroit where cats roam like bands of nomads. I flop into a comfortable chair, stare at my laptop. At a photograph of my brother. Probably one of the last pictures ever taken of him. My mind roams.

Leroi’s twelve years old. His mother, D, has remarried and moved away from Detroit—two counties north and at least as many worlds away. He spends two weekends a month with me. That’s been a struggle, an accomplishment to even get us to this point. I remember times when he missed his mother so much that he made himself sick. I remember midnight driving an hour in each direction to drop him off when staying with me was just too much for his nervous system. His eyes and nose were a runny crying mess, heaving and stammering beside me as we drove to meet D at our rendezvous spot.

I often take Leroi to hockey games and practices. I remember when his hockey bag was too big and heavy for him to pull himself. We parents would come into the locker room to prepare our kids for ice time. He’d lift up his arms and I would pull his jersey down over his chest. I used to help him snap his helmet. I used to tie his skates, stretching my fingers to pull the laces as tight as I could to support his ankles. Now I drop him off at the front door of the arena and he makes his own way to meet his teammates. The arena’s cold isn’t solely from the rink’s frozen temperature; I sometimes feel a chill when I’m the only Black parent in the stands, especially at away games.

Seven years ago, he came home from school and told us he wanted to play ice hockey. I doubt if either his mom or I had ever said the word “hockey” in the house. I don’t think we’d ever even taken him ice skating. We would be just as surprised if he came home fluent in Arabic. Where did you get that from? A couple times a year he has tournaments in distant cities scattered around the state like Traverse City or Bay City. The team stays in a hotel together. The boys eat pizza together, they run the hallways, they take over the pool area, laughing and splashing.

Laughter has always been Leroi’s love language. When Leroi was maybe five years old, he joined me at a community event I helped host at the UU Church’s memorial hall. The whole place thrummed to the DJ’s beat: seventy or eighty people eating food from local soils and roaming over the chipped linoleum floor and talking about food justice and laughing with each other and listening to poets pull thunder from their hearts.

Towards the program’s end, as people were bundling up to face winter’s wind and we started to wipe off the tables, our collective children were brought to the front of the room to do the Whip and Nae Nae. They lined up in front of a huge hand-painted banner that said “Environmental Action.” With the other children pointing and turning, prancing around him, Leroi stood straight and still, reaching for the mic. He wasn’t even tall enough to reach it on the stand. I looked up and promised him he could speak after the event was over. While we were putting up tables and chairs, he roasted us all with his best fart and poop jokes.

Now he’s a comedian only in the passenger seat of my car. My Ford Focus is cluttered with his hockey gear, wrappers from our meals on the road, sweatshirts and blankets. Salt scattered from a few winters has begun to eat away the car’s white paint. Each year more rust near the wheels. And Leroi’s approaching his teenage years. He’s much quieter in public. He’s grown into his own anxiety after his folks’ divorce. It takes him much longer to warm up to people he doesn’t know.

He says, “You were such a nerd when you were younger, Dad. Do you even have any friends.”

Mines. He knows he’s the funny one between us. Driving him to school or picking him up, going to the movies, west to Dearborn for miniature golf, a trip north to meet his mom in the Meijer parking lot, leaving the city for a weekend tournament. As soon as he closes the door, he lets loose. He loves it when I have to stop him from joking: “Boy, you’re gonna make me crash this car.” His imitation of a nerd—how does he know this is what I was (am?)—is one part vampire, one part creep, one part Quasimodo: slurring, dragging, drooling, unsuccessfully stumbling towards companionship.

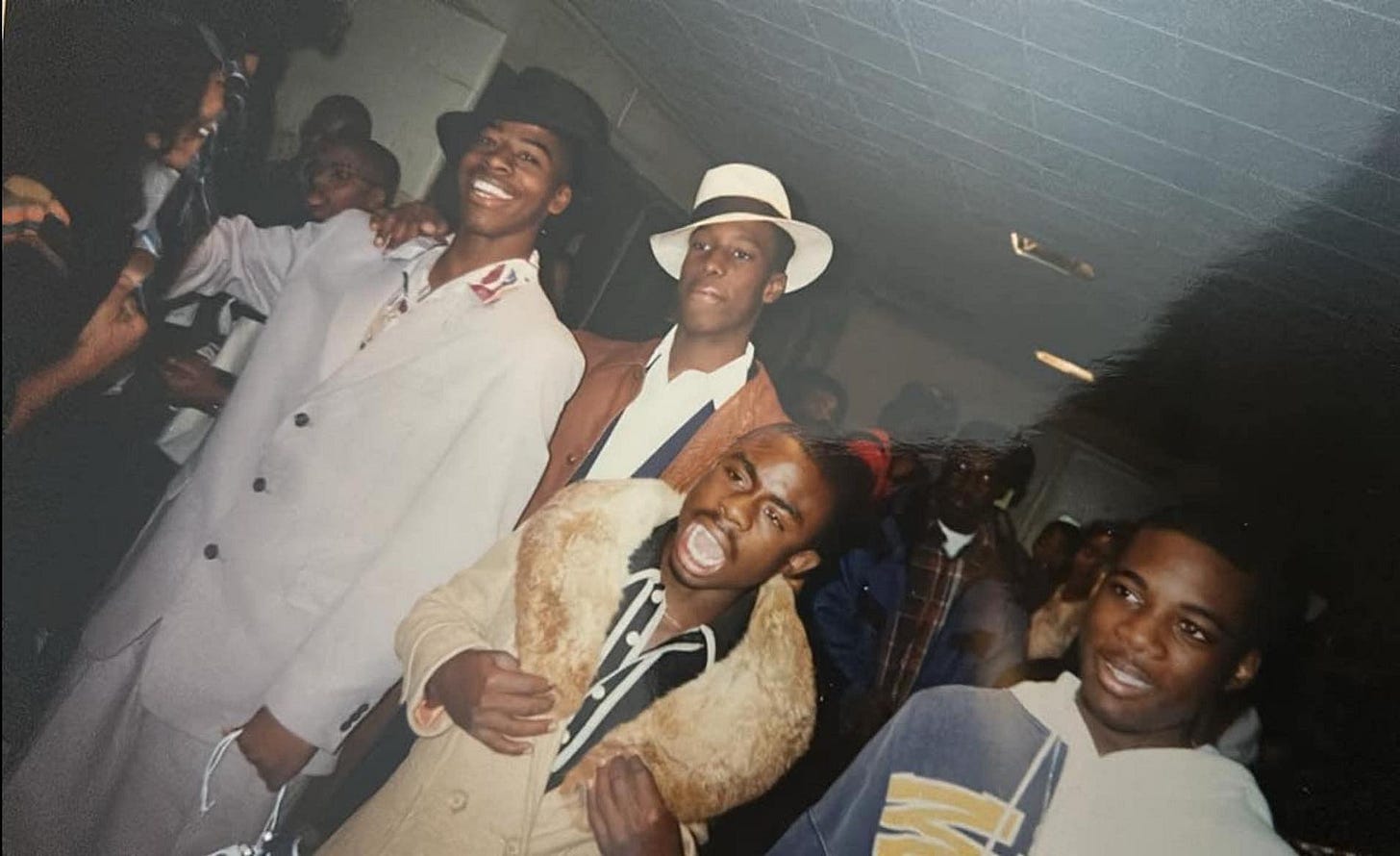

In January 2024, after what would have been my brother’s 43rd birthday, Lee’s friend Kamal messaged me a picture of him. I saved it to my computer and keep returning to it. Because I don’t have many memories, I hold tightly to the photograph, looking, looking: Lee, Kamal, and another friend, D’Juan, are in the center of a crowd; they’re lit like they’re the center of attention. He’s in high school, still alive. Above their heads are speckled square drop-ceiling tiles, the kind that were probably made of asbestos.

That picture was taken at Renaissance High School—a magnet school where kids had to test and apply to enter—a gem of Detroit’s public school system. During the 1980s, Renaissance was completely college prep. By the late 1990s, it had respected sports programs and a marching band, and my brother played drums and was on the football team. He would have graduated in 1999. The building that held his footprints—the one from that picture—was demolished and a new one erected in 2005.

What are we looking at in this picture? Is it 70s night? A pep rally? A talent show? A roasting battle? Who are these three young Black men, angels of their own realm? Did they win the costume contest? It looks like the three are parting a crowd.

Kamal is the shortest of the three. He’s wearing a tan trench coat with a fake fur collar and looks like a lion roaring. He’s popping his collar, spreading his angelic wings.

D’Juan is wearing a bright smile, a black hat, and a white suit with all three buttons buttoned.

Lee is wearing a brown leather coat. I remember this coat. Did it used to be mines? Did he wear it while I was hundreds of miles away at school? Did he wear that jacket to think about his older brother? His white fedora is tilted forward. His white collared shirt, open at the neck. His arm hangs around DeJuan's shoulders. Lee looks like their bodyguard, standing over them, their protector.

I’m lost in the look of sadness in Lee’s eyes. Is it my sadness or his I see? He looks down and away, his lips parted loosely as if he’s holding something back or holding something in. The only one in the photo not showing his teeth. Is he mourning his mother while surrounded by friends? Is he out when he was supposed to be home, steeling himself to cross the assault threshold with Father later that night? Are you at the party, Lee, or are you somewhere else altogether? Are you putting on your armor or are we seeing a glimpse underneath the protection?

That hand you put on your friend’s shoulder, Lee! The smiles all around you. Your comforting hand makes all that possible. That’s a party, flickering Black joy. For that fleeting moment, everything is going to be all right.

I talk to my brother more frequently than I ever have before, lighting candles during sacred time squeezed between sessions on my laptop. My dining room table is an altar, a writing desk, an inside joke, a gift from my dad and stepmom. The lit flame watches over this writing, my looking.

I look at that photograph again and feel a flicker of failure. I don’t know what he is thinking. Is he writing his script for how he will say goodbye, planning his own departure at the party?

A memory arises: in the front seat with my brother. I had flown home from California on a school break. I was driving my father’s Jeep, Lee riding shotgun. Running errands or driving nowhere in particular. By this time my younger brother was taller than me. I don’t think he lived long enough to get a driver’s license.

Hip hop was a love that we shared. Lee rapped on local radio shows and at high school parties. We sat side by side listening to Mobb Deep. I can’t remember what song was playing as we cruised by things we’d see every day: pizza joints, beauty shops, high schools before they were boarded up, liquor stores, Black folk watering their lawns: “as time goes by/ an eye for an eye/ we in this together, son/ your beef is mines/ so long as the sunshine can light up the sky” or “until my death/ my only goal’s to stay alive/ we living this/ to the day that we die/ survival of the fit/ only the strong survive.” We probably listened to the entire The Infamous album. Or maybe just these two raps on repeat. Two brothers listening to a hip hop duo speak rhythmically of overcoming odds: Havoc and Prodigy. Special moments together listening to words of death. The impact of the sparse drums repeat like punches and kicks.

Between my son and my brother, I feel like I am going to explode. I wish I could be closer to both of them. I feel I’m supposed to be closer. Close enough to…

To do what, I don’t know.

When our laughter dies down, Leroi asks me, “Do you even have any friends?” He means dudes. He’s steeped in the casual camaraderie of his suburban hockey team. At the team dinner, he takes a white boy’s hat. The boy chases him. They sit shoulder to shoulder, watching each other play games on their phones. Heroes who run endlessly to new levels, grabbing power objects, jumping over obstacles. Get the timing right and scoring more and more goals.

Leroi doesn’t want to pray at an altar. He doesn’t want to play tai chi with me. He doesn’t want any of my “wisdom,” just to play with his friends. He doesn’t want to answer my question “How was your day” with more than a single word. He wants to laugh and cuss in the front seat of my Ford Focus. He wants me to drive him by his former school, by the house in Detroit where all we used to live together. He asks me to reconnect with his friends’ mothers and make arrangements for them to get together.

The candle is burnt out. Now an extinguished, solitary wick. I stare at the photograph, at the memories that remain in my heart, and light a new small flame to get close enough to close the distance between us. Close enough to feel the heat’s warm fingers. I speak until the fire burns bright. The words are still staggering, dragging, tumbling slow as syrup. How many years did I miss? I’m sorry for all the times I was unable to hold him.

As the years pass, memories fall from my mind, and my son grows taller and further away. These echoes both haunt and strengthen me.

Owólabi Aboyade

(born William I. Copeland)

About the author:

Owólabi Aboyade is a multidimensional essayist/poet/critic/hip hop artist (Will See Music) from Detroit. He studies nonfiction in Pacific University’s MFA Program in Creative Writing (class of 2025). His poetry chapbook, Lee,Young Lee was published by AWE Society Press in the eventful summer of 2024. Order it here! He’s currently working on a collection of essays about grief, culture, and masculinity in gentrifying Detroit.

Heartbreaking… funny… deep… shimmering. Thank you for sharing this, Owólabi.

There is noting better than prose sung poetically. Thank you —